Wells Fargo (WFC) was founded in 1852 and is the third-largest bank in the country as measured by assets. The bank ended 2017 with about $1.3 trillion in total deposits, and its 90 different business lines collectively generated over $84 billion in revenue from a diversified mix of banking, insurance, investment, mortgage, and consumer and commercial finance services.

Unlike many big banks, Wells Fargo has little exposure to investment banking and trading operations. Instead, the firm focuses on simple lending businesses (e.g. mortgages, auto loans, commercial financing) and fee income.

The company has three operating segments:

- Community banking (57% of net income): diversified financial products and services for consumers and small businesses including checking and savings accounts, credit and debit cards, and automobile, student, mortgage, home equity, and small business lending.

- Wholesale banking (33% of net income): provides financial solutions to businesses across the U.S. and globally with annual sales generally in excess of $5 million. These include Business Banking, Commercial Real Estate, Corporate Banking, Financial Institutions Group, Government and Institutional Banking, Middle Market Banking, Principal Investments, Treasury Management, Wells Fargo Commercial Capital, and Wells Fargo Securities.

- Wealth & Investment Management (10% of net income): provides a full range of personalized wealth management, investment, and retirement products and services to clients across U.S.-based businesses including Wells Fargo Advisors, The Private Bank, Abbot Downing, Wells Fargo Institutional Retirement and Trust, and Wells Fargo Asset Management. Services include financial planning, private banking, credit, investment management and fiduciary services to high-net worth and ultra-high-net worth individuals and families.

In 2017 Wells Fargo’s loan book of $957 billion was rather evenly divided between commercial loans (53%) and consumer (47%). The company serves over 70 million customers through its network of more than 8,300 store locations and 13,000 ATMs, as well as its website and mobile banking application.

Business Analysis

Banks primarily gather deposits and loan them out for interest income. As borrowers, consumers and businesses are most concerned with getting access to dependable financing at the lowest interest rate possible.

In other words, banks are largely commodity businesses, and the lowest-cost operator usually survives the longest in commodity markets. As one of the biggest banks in the country, Wells Fargo enjoys numerous cost advantages, which begin with its track record of gathering low-cost deposits from consumers and businesses that it can lend out at higher interest rates.

According to Wells Fargo’s annual reports, the company’s total deposits have grown from $3.7 billion in 1966 to $1.3 trillion in 2017, representing approximately 12% annual growth over that period. Wells Fargo’s deposits have continued growing at a healthy mid to high-single digit rate in recent years as well.

The company has more retail deposits than any other bank in the country and is ranks in the top five banks in terms of total deposits. When combined with company’s conservative lending practices, which generate a predictable stream of higher-yielding cash flows, it’s no surprise that Wells Fargo is famously Warren Buffett’s favorite bank.

In fact, Berkshire owns nearly $30 billion worth of Wells Fargo stock (over 9% of the company), making it one of Buffett’s largest equity holdings. And in the past, Charlie Munger, Buffett’s right-hand man at Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.B), has called Wells Fargo his favorite company period, against which all others should be measured.

That’s thanks to the bank’s long-term track record of highly conservative and trustworthy banking practices. These have allowed the bank to quickly and consistently grow, while dodging the numerous industry, economic, and global events since its founding in 1852 (see below) that have caused thousands of its rivals to close:

- 12 banking crises

- 27 recessions

- Three depressions

- Two world wars

- A global flu pandemic that killed over 3% of the global population

In fact, Wells Fargo’s conservative lending practices have allowed it to remain one of the most consistently profitable large U.S. banks, even during periodic industry crises.

For example, during the financial crisis Wells Fargo’s relatively small exposure to toxic mortgage debt and credit default swaps allowed it to not only survive largely unscathed, but actually remain profitable. That’s because, even at the peak of the crisis, loan losses only amounted to 2.71% of assets. Only JPMorgan Chase (JPM), which also followed a highly conservative banking strategy, was able to repeat this feat.

Basically, Wells Fargo has chosen to largely ignore faster-growing but more volatile businesses, such as investment banking (trading made up just 2% of net income in 2017), in favor of operating like America’s largest regional bank.

However, Wells Fargo’s industry-leading balance sheet was just one part of the company’s strong long-term investment thesis. The other two attractions were its ability to grow faster than its peers (but with lower risk) and achieve some of the top profitability in the industry.

Its edge in terms of profitability was largely due to its advantages against rival regional and community banks. First and foremost, Wells Fargo’s giant scale allowed it to achieve massive operational leverage, thanks to some of the lowest cost capital in the industry.

For example, 20% of the bank’s massive deposit base (which it lends out) bear no interest at all. This is why the bank’s overall interest cost as a percentage of assets is just 0.3%. Thanks to its cheap funding base, Wells Fargo is virtually guaranteed to generate a positive return on its loan portfolio despite today’s low interest rate environment.

Meanwhile, Wells Fargo was able to grow quickly, thanks to rapid industry consolidation over the past few decades. In fact, Wells Fargo now serves about one in three households in the U.S., and its convenience and brand recognition are two reasons why it has enjoyed such strong deposit growth.

The company maintains industry-leading distribution channels, including storefronts, ATMs, online, and mobile, for example. This allows Wells Fargo to serve customers in more locations than any other bank, creating stickier and longer-lasting customer relationships.

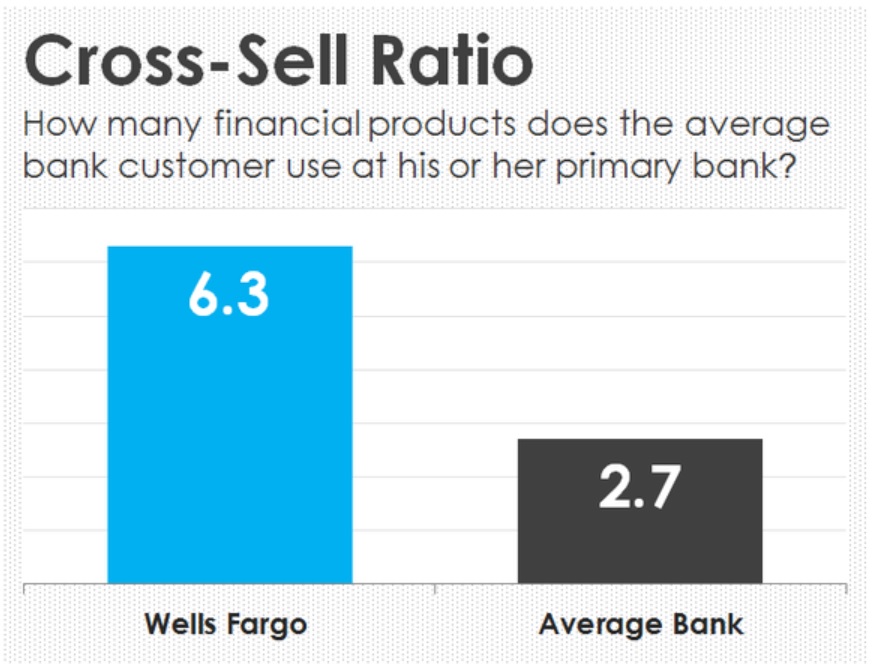

These factors helped the bank become the industry’s unquestioned leader in cross-selling numerous products to customers (more on this in a moment), helping it achieve the best returns on equity and assets of any large U.S. bank. The end result was very strong earnings and dividend growth, which historically made Wells Fargo one of the best long-term investments in banking.

While the bank is working through some challenges, it still appears to have a large moat. The company gains competitive advantages from its substantial scale, low-cost deposit base, strong capitalization, and leading market share positions.

Despite Wells Fargo’s impressive past track record, the bank has recently fallen from grace, and in a big way.

Key Risks

There are numerous risks associated with Wells Fargo, including a few potentially major concerns for the bank’s long-term growth prospects.

We need to consider that historically Wells Fargo has grown quickly via two main methods. The first was through aggressive industry consolidation of smaller regional banks, including:

- $11.6 billion acquisition of L.A.-based First Interstate Bancorp in 1996.

- $31.7 billion merger with Minneapolis, Minnesota-based Northwest Corporation in 1998.

- 19 small to medium-sized regional banks acquired between 1999 and 2001 (that were hurt during the 2000 recession and tech bubble implosion).

- Five acquisitions between 2007 and 2008, including the $15.1 billion purchase of Wachovia, which had just failed due to toxic subprime debt made during the housing bubble.

It’s important to realize that going forward, Wells Fargo is very unlikely to receive approval from regulators to make ongoing acquisitions under a much stricter regulatory regime that is more worried about banks being “too big to fail.”

Furthermore, some of these purchases have come back to haunt the company. Specifically, the merger with Northwest saw key top Wells Fargo executives replaced by Northwest ones, most notably Northwest CEO Dick Kovacevich. Mr. Kovacevich took the company’s corporate culture down a treacherous path, one that brings us to the next major growth risk for the bank.

Part of what allowed Wells Fargo to grow so quickly, while focusing on more traditional and less risky banking businesses, was its historically high cross-sell ratio. This was a policy that had been started by Wells Fargo’s previous CEO’s but was ramped up to an extreme under former Northwest alumni Kovacevich and John Stumpf.

Specifically, the goal was to make Wells Fargo the hands-down best bank at cross-selling its customers numerous services. Having customers take at least several financial products, such as checking and savings accounts, credit cards, personal loans, home equity loans, mortgages, and insurance services, was simply a stickier and more lucrative strategy for the company.

In fact, previous CEO John Stumpf famously had a long-term goal exemplified by the corporate motto “8 is great,” meaning that he ultimately wanted Wells Fargo to achieve a cross-sell ratio of 8 products per customer.

Under Stumpf, Wells Fargo embarked upon its now-infamous practice of strictly enforcing products sales quotas from its employees, sometimes under the threat (often carried out) of job termination if they failed to meet them.

Employees have described this as a pressure cooker and “boiler room” like work environment that ended up resulting in numerous highly unethical and even illegal sales practices, including:

- An independent third-party review of the bank’s accounts revealed that the total number of unauthorized accounts opened was actually 3.5 million, 67% more than initially thought.

- The bank incorrectly charged 800,000 car loan customers for unnecessary insurance that, according to Wells Fargo, could have caused around 20,000 customers to default on their payments and have their vehicles repossessed.

- Wells Fargo Merchant services apparently overcharged thousands of small businesses for credit card processing due to “deceptive language” in its 63-page service contract.

- 110,000 customers were inappropriately charged “mortgage rate lock extension fees” for missing mortgage payments that were actually a result of Wells Fargo’s initiated payment processing delays.

- In October 2017, regulators fined Wells Fargo $3.4 million for recommending clients invest in volatility-linked hedge investments that were “highly likely to lose value over time.”

With that said, the rest of the banking industry isn’t exactly filled with angels either (not that it makes Wells Fargo’s behavior any less despicable). Banks have paid over $200 billion in fines and settlements since 2009. Another article puts the figure even higher.

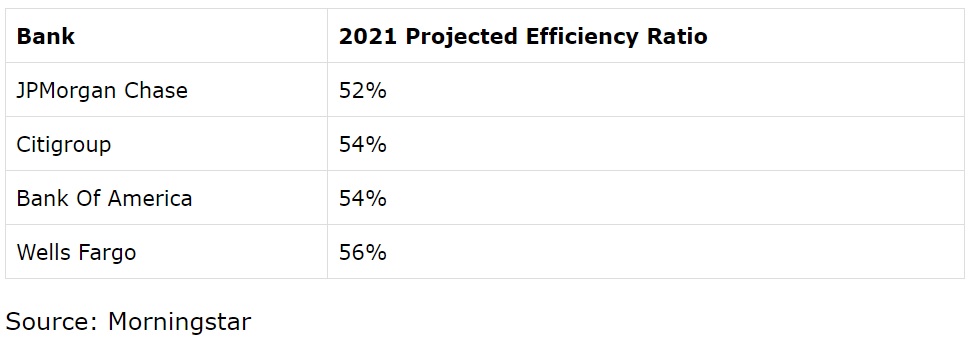

Wells Fargo was historically the “cleanest” of its big bank brothers, but the ongoing series of scandals has resulted in fines of about $200 million so far, the resignation of CEO John Stumpf (replaced by COO John Sloan), and $3.25 billion in legal expenses in 2017. These giant legal bills have caused Wells Fargo’s once industry-leading efficiency ratio (expenses/revenue) to soar to 76%, compared to about 55% before the scandals came to light.

Now it is true that this giant spike in costs is likely temporary, and indeed analysts expect that the bank’s ongoing cost-cutting measures (and an eventual end to legal costs) will eventually return it to its former low-cost operations.

However, note that Wells Fargo’s mega bank rivals are also streamlining at an impressive rate. In fact, they are expected to ultimately become leaner and more profitable. In other words, Wells Fargo’s investment thesis, that it was the safest, most profitable, and fastest-growing large bank, is at risk of losing yet another one of its cornerstones.

Additionally, since the scandals first broke in the third quarter of 2016, Wells Fargo’s growth in tangible book value (the objective value of the bank’s net assets) has decelerated from a healthy mid-single-digit pace to closer to 2%, underperforming most of its peers.

Part of this performance can be chalked up to short-term declines in new customer acquisitions and account openings due to bad PR. In addition, the high legal costs have certainly taken their toll but are likely to be temporary.

However, there is a real risk that Wells Fargo’s long-term industry-leading growth is now a thing of the past, due to two reasons. First, under John Sloan, Wells Fargo has ended its cross-selling quota system, so naturally its cross-selling ratio has begun to decline. This is being called a long-term (and necessary) change to the corporate culture and potentially represents a permanent impairment to Wells Fargo’s long-term growth potential (i.e. its impressive historical growth figures were inflated and won’t be repeated going forward).

Part of this might come from a loss of reputation as well, leading to less customer loyalty. For example, Wells Fargo used to command the highest customer satisfaction ratings of any large U.S. bank, but JD Power’s 2017 satisfaction survey found that its rating had fallen to 7th in the nation. Wells Fargo’s rating was below the average for regional banks, as well as below that of JPMorgan and Bank of America (BAC).

In addition, the sheer number of scandals coming to light has resulted in regulators at the Federal Reserve (which regulates U.S. banks) doing something unprecedented in the history of U.S. banking. On February 2, 2018, the Fed announced it is forcing Wells Fargo to replace three board members by April, and a fourth by the end of the year.

More importantly, due to “persistent and pervasive misconduct…Until the firm makes sufficient improvements, it will be restricted from growing any larger than its total asset size as of the end of 2017.”

Wells Fargo expects the action will reduce its profits by $300 million to $400 million in 2018 (compared to more than $20 billion in net income) but is confident it will satisfy the requirements of the consent order it agreed to with the Fed. The order is not related to any new matters, but to prior issues where Wells Fargo is working to make progress.

The Fed’s actions are not expected to affect the bank’s financial condition, and Wells Fargo’s dividend should remain safe. The company expects to get the restrictions lifted within the next year, hopefully minimizing the impact of the penalty.

However, Wells Fargo was already struggling to grow its top and bottom lines during its ongoing scandals. That’s even despite a very favorable economic and rising interest rate environment that has seen sales, and most notably profits, at its major rivals soar to all-time record levels (higher than even the speculation-fueled boom times of 2007).

Now, the bank is literally been blocked from growing its asset base, for an unknown period of time. As a result, Wells Fargo’s near-term growth prospects have fallen significantly, and all earnings growth will have to come from rising net interest margin spreads (the difference between Wells Fargo’s borrowing costs and the rate on loans it makes), as well as cost-cutting initiatives.

However, because of Wells Fargo’s loan mix (more heavily skewed towards fixed rate mortgages), Wells Fargo’s net interest margin spread hasn’t been growing in recent years. That’s despite rising interest rates that have fueled slow but steady net interest margin gains at rival banks.

As a result, Wells Fargo’s revenues are potentially going to have a hard time growing, at least until the Federal Reserve’s cease and desist order is lifted. Fortunately, the bank has said it plans to cut costs by $4 billion in 2018 and 2019. If those targets are met, than Wells Fargo’s net income should still grow about 20%.

But for dividend investors, there are still two problems. First, U.S. banks aren’t allowed to return cash to shareholders (via buybacks and dividends) without first undergoing an annual stress test and submitting a Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review, or CCAR, to the Fed each year.

Recently, the Federal Reserve has implied that it wants banks to have a much more conservative earnings payout ratio near 30%. In 2017, Wells Fargo’s payout ratio was 38%, significantly higher than the Fed’s target. Even with tax cuts benefiting its bottom line in 2018, the company’s payout ratio will remain above 30%.

What’s more, whether or not a bank’s CCAR is approved (in terms of how much cash it can return that year) depends on the results of the annual stress test results.

The stress test is something the Fed puts the country’s largest and most strategically important (“too big to fail”) banks through. It simulates a severe global economic recession to see how a bank’s assets will hold up in order to minimize the chances of another global financial catastrophe that puts the world’s economy at risk.

The Fed has just released 2018’s stress test scenario, and it’s much more conservative than in past years. That means it simulates a far longer and more severe global recession, one that assumes:

- The recession lasts three years (Great Recession lasted 1.5 years)

- U.S. GDP falls 7.5% (GDP fell 5.1% during the Great Recession)

- Unemployment rises to 10% (same as Great Recession peak)

- Stock market falls 65% (Great Recession peak to trough was 54%)

- Home prices fall 30%

- Commercial real estate prices fall 40%

- Concurrent severe recessions in the U.K., E.U., and Japan, and mild recession in developing Asian economies (during Great Recession China’s economy still grew)

This much tougher simulation means that banks are likely to be approved for smaller increases in their capital returns in 2018, which bodes poorly for Wells Fargo’s already slow-growing dividend (which increased just 2.6% in 2017).

In addition to all these ongoing problems (not shared by other increasingly conservative, safe, and faster-growing rivals like JPMorgan Chase), Wells Fargo still faces the problem that it operates in an inherently cyclical industry, one whose profits are volatile and rise and fall with the health of the economy.

The current U.S. expansion is now in its 9th year, the second longest in U.S. history. Should the next U.S. recession arrive sooner rather than later (no one knows), Wells Fargo’s earnings will get hit from rising unemployment triggering a decline in lending demand and rising default rates.

While bank stocks would underperform in such an environment, their long-term earnings power shouldn’t be affected. Importantly, banks are also much better capitalized than they have ever been as a result of new regulations. Here is what Buffett said about banks in a 2013 interview:

“The banks will not get this country in trouble, I guarantee it. The capital ratios are huge, the excesses on the asset side have been largely cleared out. Our banking system is in the best shape in recent memory.”

Today U.S. banks are currently experiencing a golden age, one where rising interest rates, an accelerating economy, generally loosening regulations, and strong increases in consumer and business lending are fueling very healthy earnings and dividend growth.

However, due to its scandals, and the current Federal Reserve cease and desist order, Wells Fargo is hardly growing at all. The company effectively has its sails down while the growth winds are at its industry’s back, and its rivals are all surging past it in terms of growth, profitability, and even balance sheet safety.

Wells Fargo increasingly looks like a bank whose best days may be behind it. That’s thanks to a growing number of self-inflicted wounds and rising growth risks that hamstring its competitiveness with its large and increasingly impressive rivals.

Investors may therefore decide to reduce the safety and quality valuation multiple premium historically enjoyed by the stock.

Bank stocks trade at a multiple of book value. Companies perceived to have riskier balance sheets and operations usually trade below book value, while banks perceived to be the safest and highest quality trade above book value.

For example, Deutsche Bank, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo currently trade at price-to-book ratios of 0.4, 1.3, 1.7, and 1.6, respectively.

For more than a decade, Wells Fargo’s price-to-book ratio has never fallen below 0.5. According to Gurufocus, Wells Fargo’s median price-to-book ratio over the last 13 years has been 1.5.

If the company’s long-term growth prospects and profitability are permanently impaired thanks to its sales scandal and tighter regulatory oversight, Wells Fargo’s stock could continue struggling as its premium valuation multiple compresses to reflect the bank’s new normal.

Closing Thoughts on Wells Fargo

Wells Fargo was once famous for having the industry’s best growth, strongest balance sheet, highest profitability, and most conservative management team. However, at least in the short-term, the ongoing and seemingly ever-expanding series of scandals has caused all four of these pillars of its investment thesis to crack.

The bank fortunately remains highly profitable in this industry boom time, especially thanks to the new tax cuts, and the company’s dividend remains safe. With that said, investors need to realize that many of the problems ailing Wells Fargo, particularly slow top line, bottom line, and dividend growth, could persist for many years. The bank’s long-term growth rate could also be permanently lower if illegal cross-selling practices were indeed a primary drive of company-wide growth over the past decade. Only time will tell.

Given the continued improvements at its rivals, most notably JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, it is looking increasingly possible that Wells Fargo might no longer be the best large bank in America. While long-term investors (such as Warren Buffett) might not necessarily need or want to sell their shares, it’s hard to recommend Wells Fargo for new money today.

To learn more about Wells Fargo’s dividend safety and growth profile, please click here.

Leave A Comment