Founded in 1833, Royal Dutch Shell (RDS.B) is one of the world’s largest integrated oil companies with operations in over 70 countries. In addition to exploring for and extracting crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids, Royal Dutch Shell owns a number of refineries, distribution terminals, and LNG tankers.

The company also has a midstream master limited partnership (MLP) called Shell Midstream Partners (SHLX). This is used to monetize its North American midstream (storage, transportation, and processing) facilities. Shell owns 44% of Shell Midstream’s common units, a 2% general partner stake, and its lucrative incentive distribution rights (IDRs). Thanks to this structure, about 70% of Shell Midstream’s cash flow comes back to the parent company.

Shell operates through three segments:

- Integrated Gas (43% of operating income): LNG operations

- Downstream (30% of operating income): refining and petrochemical

- Upstream (27% of operating income): oil & gas production

Note that Shell has a dual share structure, with class A shares domiciled in the Netherlands and B shares domiciled in the U.K. for tax purposes. Until recently, this meant that A shares faced a 15% Dutch tax withholding that had to be recouped by the U.S. foreign dividend withholding tax credit. The U.K. doesn’t have foreign dividend withholdings (except for REITs).

However, the Netherlands has started phasing out its withholding (currently at 5%) and by January 1, 2020, will withhold no taxes on dividends. This means there will soon be no effective difference between Shell’s class A and B shares.

Business Analysis

The oil industry sells commodity products, meaning there is effectively no pricing power (all oil companies are price takers). Furthermore, the price of its products is set in global markets where prices can be incredibly volatile. For example, in the 2015 oil crash prices plunged 76% from peak to trough.

These two factors create extremely erratic sales, earnings, and cash flow. In fact, Shell’s revenue dropped by 37% in 2015. Therefore, you might assume that oil companies are a poor source of safe and rising dividends. However, Shell has managed to generate one of the industry’s most impressive dividend track records, including uninterrupted payouts since World War II. There are three reasons for this.

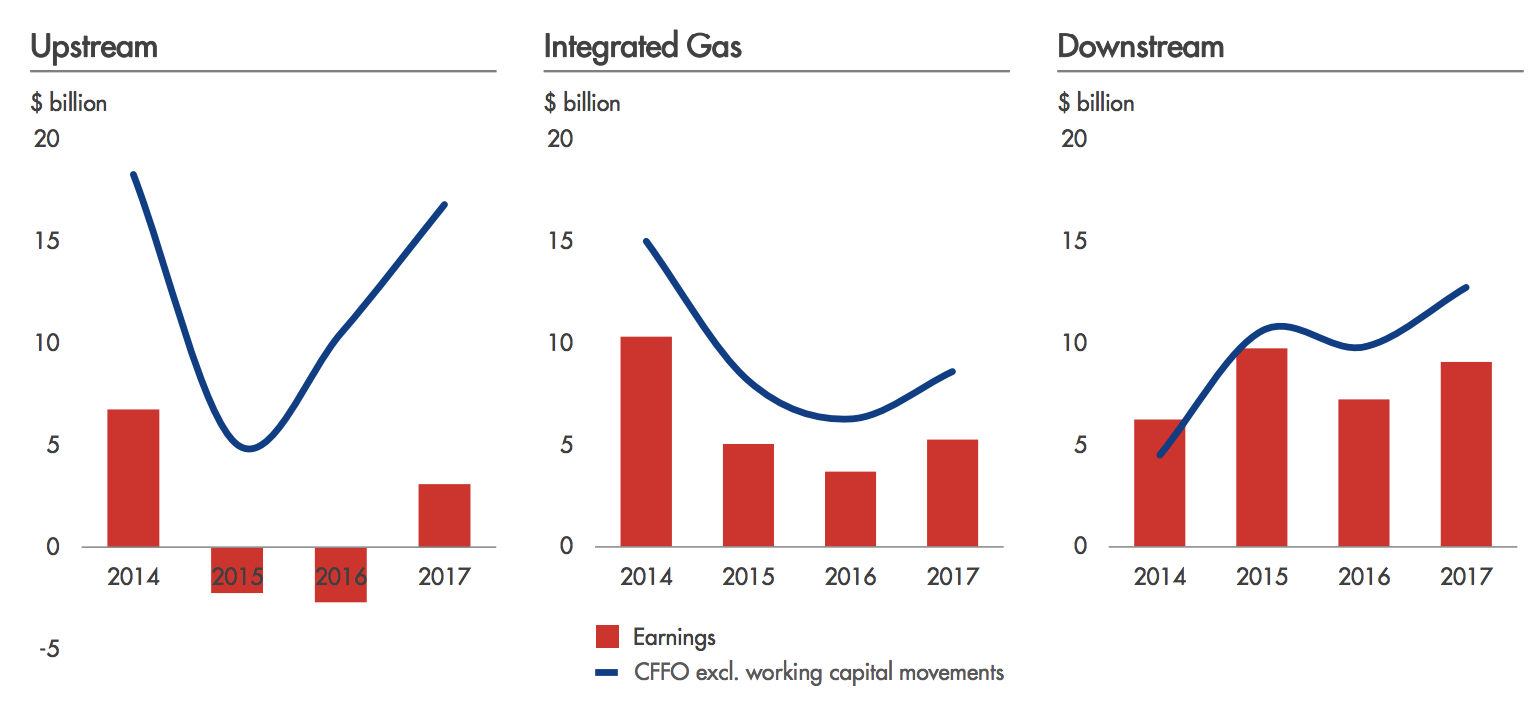

First, Shell’s integrated nature means that it is able to somewhat reduce the volatility of its earnings. This is because when oil & gas prices fall, the profitability of its downstream (refining and petrochemical) operations increases, due to lower input costs.

As importantly is the company’s proven ability to adapt to changing industry conditions over time. For example, in response to the oil crash Shell slashed its capital spending by 40% from 2014 to 2017. It also reduced its per barrel production costs by 35% over that time, saving the company $6 billion per year. Finally, the company sold off non-core assets, including $40 billion worth between 2016 and 2020.

Proceeds from these sales were used to cover its ongoing spending costs (guidance of $25 billion in 2018), as well help maintain its dividend. Going forward, management is pursuing a strategy that it believes will lead to more stable and steadily growing free cash flow over time.

Specifically, the company is planning for a “lower for longer” oil price regime, basing its investment plans for a long-term global oil average of $60 per barrel. The company has refocused its capital spending to focus on less complex projects, which are easier to bring online on time and on budget. They also start generating cash flow sooner, helping to boost the company’s returns on invested capital.

Shell currently has over 50 projects either under construction, or in the late planning stages. These are expected to increase oil production by 1 million barrels per day (25%) and liquified natural gas (LNG) capacity by 50%.

Why is Shell focused twice as much on gas as oil? Because of two key factors that make for superior economics. First, gas is a far more stable cash flow source for the company. Gas production decline rates can be much lower than oil decline rates, meaning that once a gas field is set up it takes less marginal investment to maintain production, resulting in steadier cash flow and higher profitability.

Second, Shell’s LNG business frequently involves the use of very long-term contracts, sometimes up to 20 years in duration. These are fixed-rate deals with annual inflation adjustments. They represent the polar opposite of the company’s oil business where cash flow fluctuates wildly.

However, Shell’s LNG-focused growth plans aren’t just centered around creating LNG but controlling the entire supply chain. That’s why in 2015 Shell purchased BG Group, the world’s largest producer and shipper of LNG in the world, for $70 billion. That deal turned Shell into the world’s dominant LNG producer and transporter, with a fleet of over 90 LNG tankers representing about 20% of the global fleet.

Shell is investing heavily into LNG because of several important global energy trends. First, fast-growing emerging markets such as China have enormous energy needs, including gas for industrial purposes. In addition, due to environmental concerns (the worst air quality in the world), nation’s such as China and India are quickly attempting to switch from coal power to gas fired electrical generating capacity.

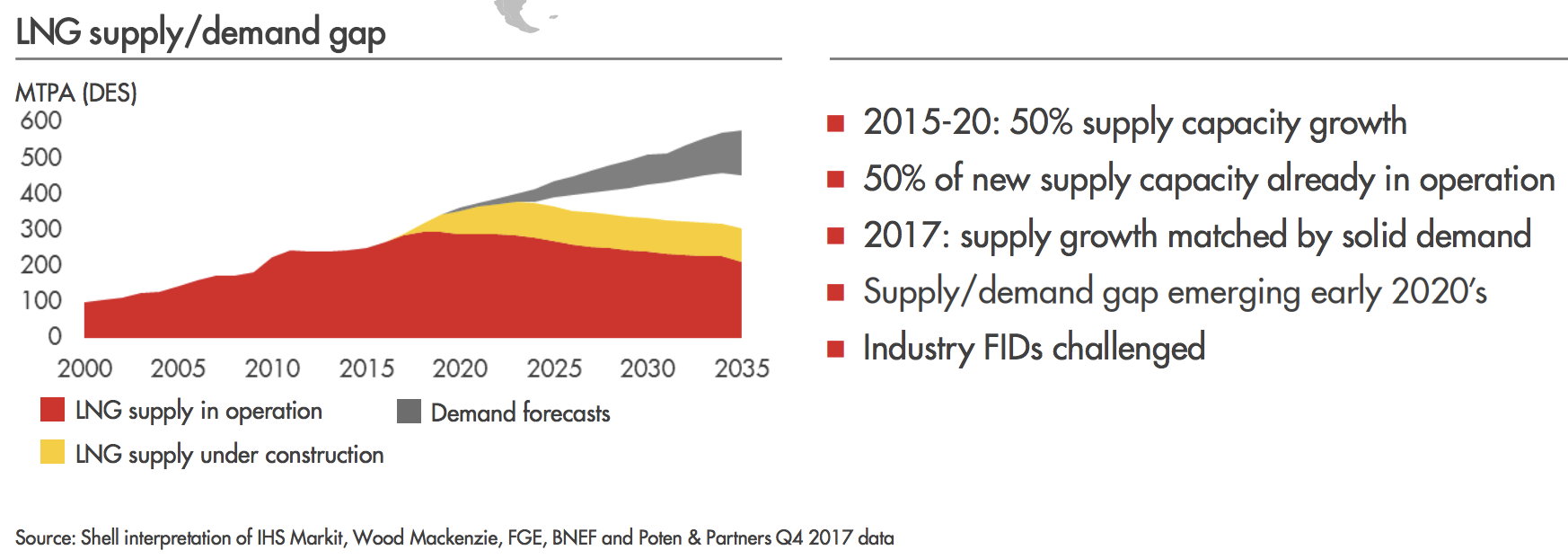

This is why Shell estimates that global LNG demand will grow by about 4% per year for the foreseeable. That’s twice the rate of global gas demand (2% annually) and four times the rate of oil demand (1% annually). As a result, LNG demand is expected to outstrip supply by the early 2020s.

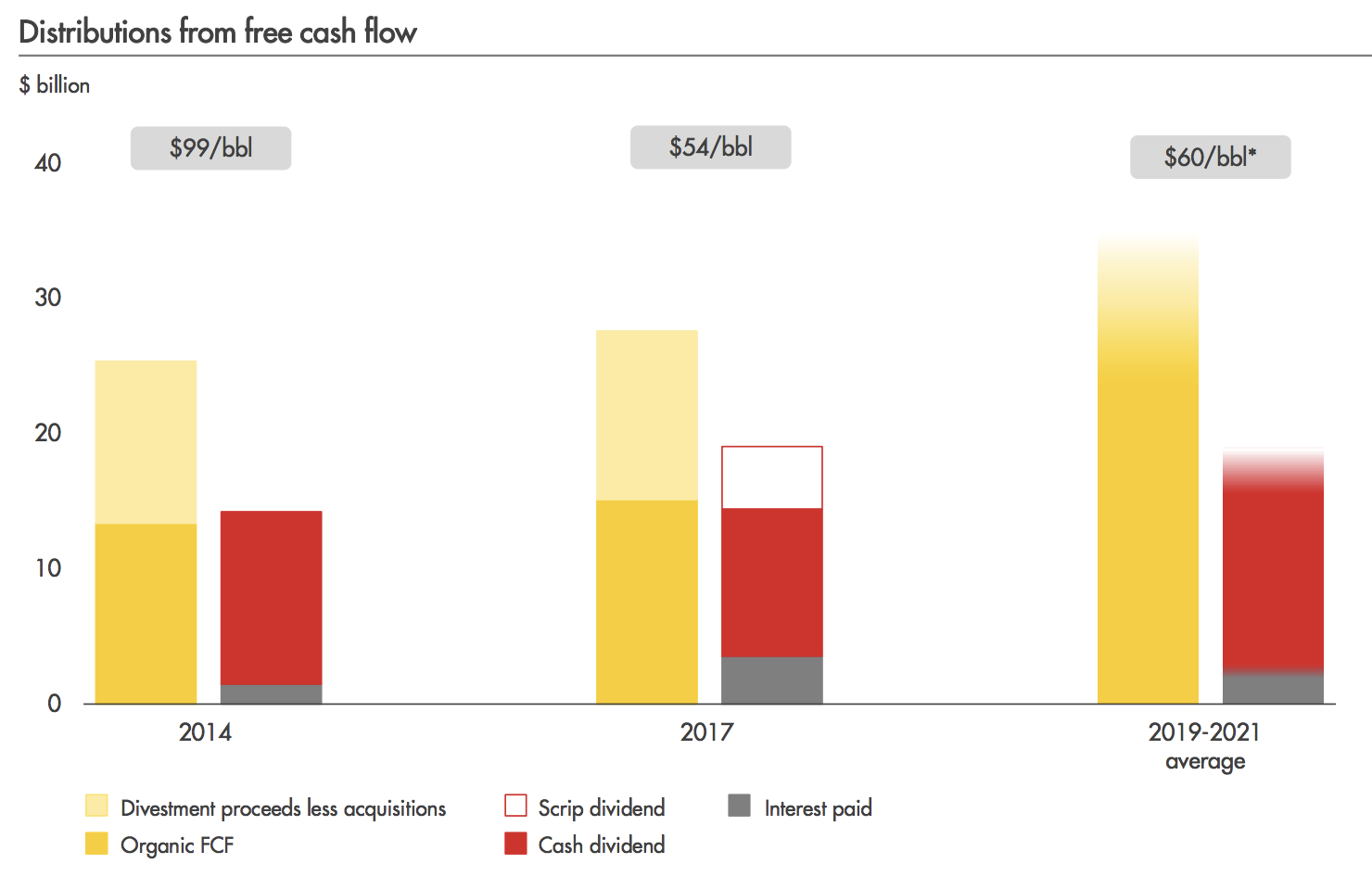

Management expects the company’s current growth plans to significantly boost the firm’s cash flow in the coming years. In fact, at a Brent oil price (global standard) of $60 per barrel Brent oil price by 2020, Shell expects to be generating about $32.5 billion in free cash flow, and retain about $21.5 billion of that after paying its dividend.

Shell estimates that for each $1 change in the price of Brent its cash flow will increase or decrease by about $600 million per year, so these figures can swing around significantly. However, it is clear that the company has significantly improved its ability to cover its dividend with organic free cash flow in a lower oil price world.

Should the price of oil remain well above Shell’s breakeven point, management plans to use retained free cash flow to pay down debt (taken on during the oil crash) and buy back shares (at least $25 billion worth through 2021). Buybacks are meant to offset share dilution associated with the BG Group acquisition.

A strong balance sheet is essential to any integrated oil company, especially one that is known around the world for its decades of safe and steady dividends. This is because during the inevitable periods of low oil prices oil majors have to borrow heavily to invest in maintaining and expanding production, as well as to pay their dividends.

Fortunately, Shell maintains a very strong balance sheet as demonstrated by its A+ credit rating from Standard & Poor’s. The company should not have trouble continuing to borrow at very low interest rates.

However, due to the cyclical nature of its business, Shell still plans to make repaying its debt the top priority. By 2021 management says it will reduce its net debt / capital ratio to 20% from about 25% today. That will help ensure that in any future oil crash Shell will be able to borrow cheaply enough to maintain both its business and its dividend.

So with Shell’s future growth plans centered around less cyclical LNG and its free cash flow set to grow nicely in the coming years, that makes the company a great high-yield income growth stock, right?

Well, not necessarily. As impressive as Shell’s dividend track record is, and despite the firm’s strong potential for future payout growth, there are still several risks to keep in mind that might make Royal Dutch Shell a suboptimal investment.

Key Risks

First, it should be noted that while Shell is famous for its very steady payouts over time, the growth rate is not nearly as impressive. For example, over the last 20 years Shell’s average dividend growth rate has been about 2% per year, which means that it has basically kept up with inflation.

In addition, while Shell has never technically cut its dividend since 1945, during the oil crash it did start paying the dividend in stock instead of cash (now back to cash dividends). This means that any shareholders counting on cash income (like retirees living off dividends) suffered income disruption during the latest industry downturn.

And while the cyclical nature of the oil & gas industry explains some of that slow growth, Shell’s major U.S. rivals, Chevron (CVX) and Exxon Mobil (XOM), have managed to grow their dividends every year for the last 32 and 35 years, respectively. They also continued paying cash dividends (rather than in stock) during the oil crash, and their long-term dividend growth rates have been much stronger.

Simply put, while Shell has done a relatively good job of maintaining a disciplined focus on investment and a strong balance sheet, both of its American peers have outperformed it by a wide margin.

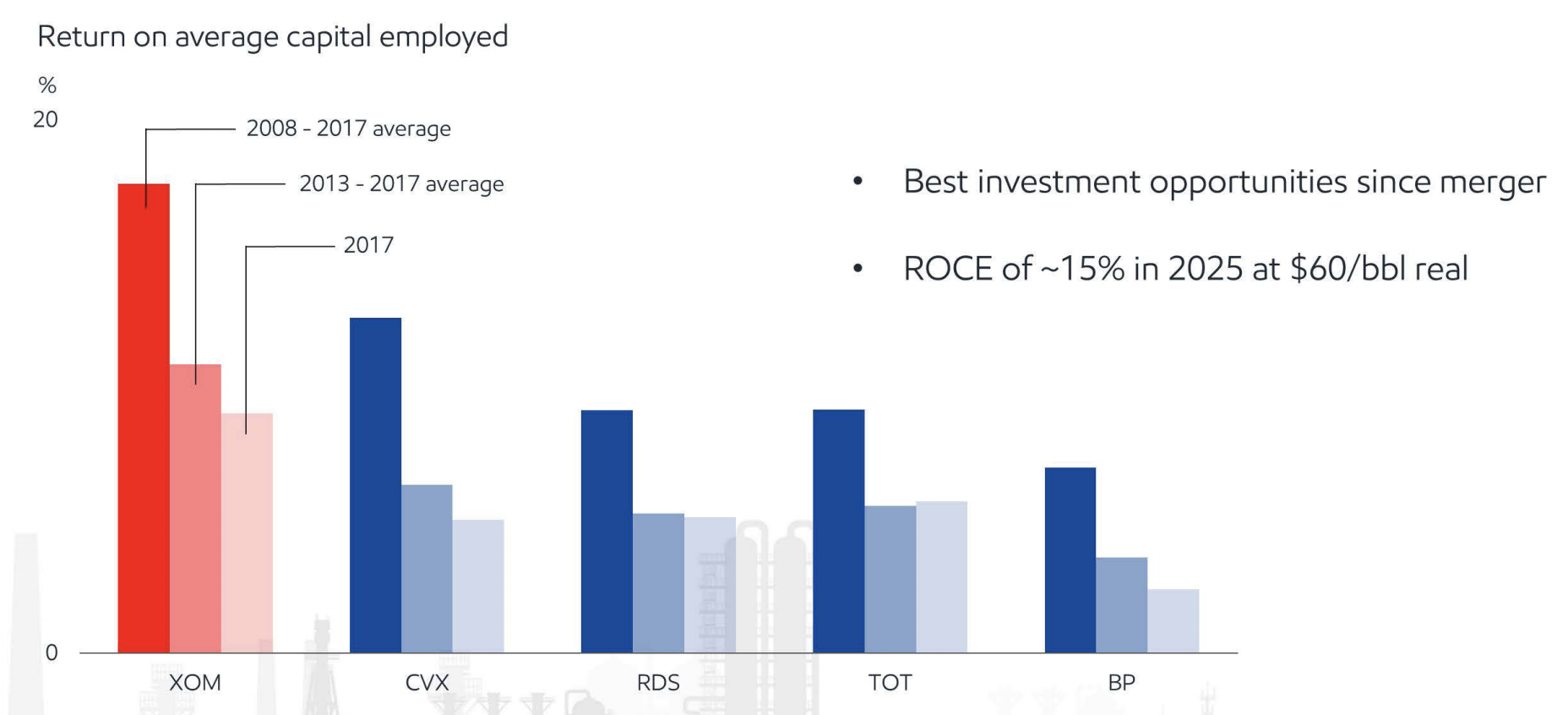

For example, the best proxy for quality management and good long-term capital allocation is return on invested capital (in the oil industry it is called return on capital employed). In the past decade, Exxon and Chevron have had the best returns on capital of any of the five oil majors. As importantly, they’ve suffered the least impairments, or losses on previous investments and acquisitions.

While Shell has historically suffered the least impairments of its European peers, it’s 10-year average return on capital has also been relatively poor. Now it should be noted that Shell is targeting 10% returns on capital by 2020, marking an improvement from its low historical levels. However, that level is still beneath the 15% that Exxon is targeting and the close to 20% that analysts expect Chevron to be able to achieve (Chevron is expected to become the most profitable oil major).

Shell’s new corporate strategy will take time to prove out under its CEO Ben van Beurden, who took over in 2014. Perhaps most importantly, the rich price Shell paid for BG Group might mean that it takes a long time for that mega acquisition to prove profitable to shareholders.

Another thing to consider is that Shell has historically struggled to replace its reserves during times of low oil prices. For example, between 2015 and 2017 its average reserve replacement ratio (new discoveries/production) was just 78%.

Good oil companies are careful to maintain reserve replacement ratio (RRRs) of over 100% consistently to allow them to maintain and grow production over time. The reason for Shell’s low RRR (just 27% in 2017) is the drastic cut to its exploration budget it undertook during the oil crash, as well as the divestitures it needed to make to protect its balance sheet.

In contrast, Exxon and Chevron have average 10-year RRRs of over 100%, and Chevron was able to achieve 162% reserve replacement in 2017. This is just another way in which American oil majors have demonstrated superior long-term capital allocation to their European peers.

Another risk to Shell’s long-term plans are the changing nature of the LNG market which is at the heart of the company’s new growth strategy.

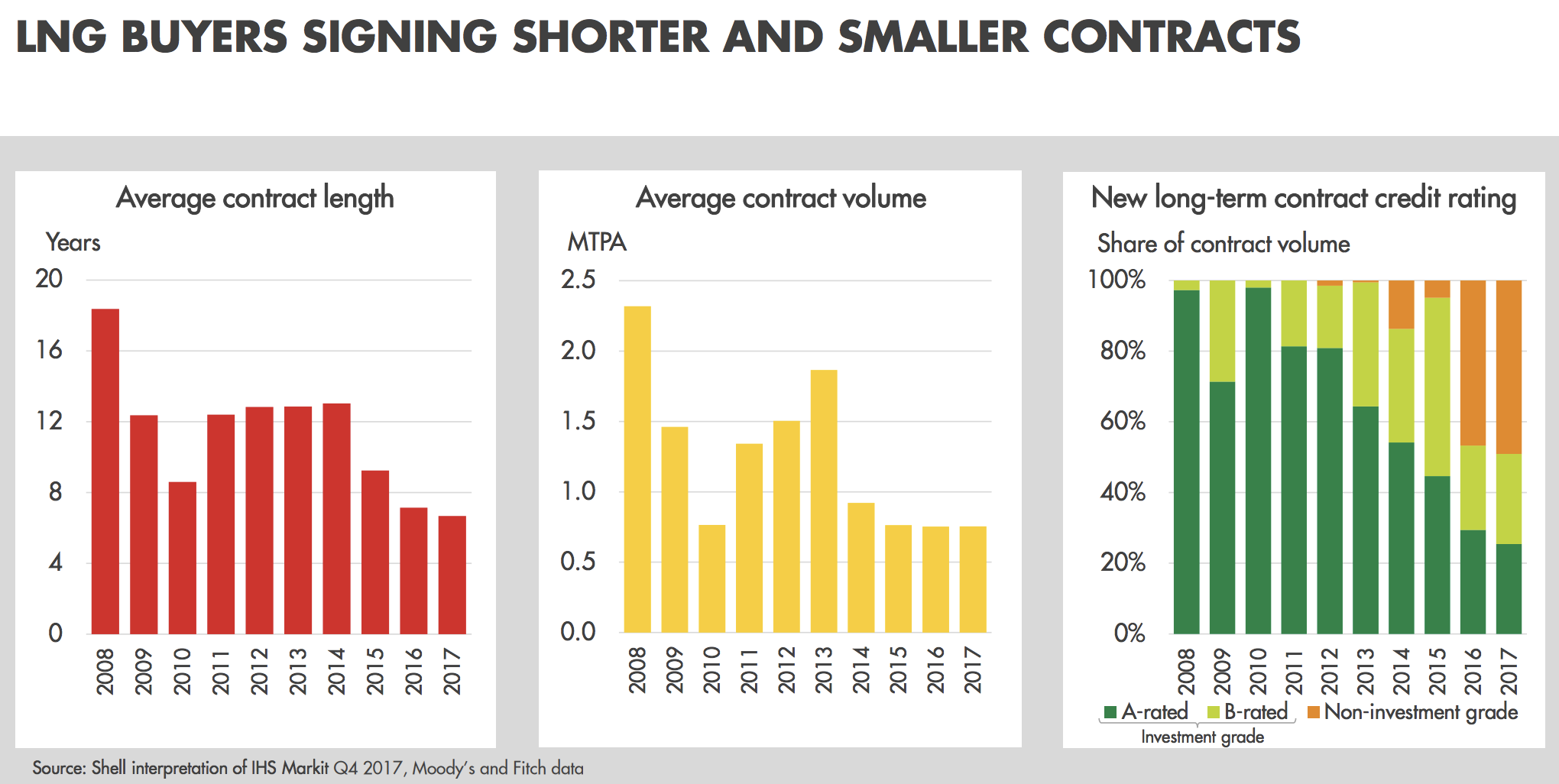

In the past, LNG contracts were usually for very long terms, with most spanning almost two decades. However, in recent years as more oil companies have entered the space, increased competition has caused average contract durations to fall drastically.

In other words, some of the key benefits (e.g. stable cash flow) that were a large reason for Shell’s big push into LNG are now declining. It’s still true that multi-year contracts provide superior cash flow stability compared to more oil-focused peers; however, the decline in average contract term shows the challenge associated with long-term planning in this industry.

Which brings us to the biggest risk of all for any oil major. Specifically, the global oil & gas markets are incredibly complex. Prices are set at the margin, but impacted by dozens of hard-to-predict factors.

Oil companies have to plan their substantial capital spending budgets many years in advance. Those decisions are based on management’s best guesstimates about the long-term average oil price (LNG is usually index to oil as well).

However, as you can see in the figure below, the potential range of future oil prices is extremely wide. For example, ConocoPhillips’ (COP) proprietary models show that the average oil price through 2025 could range anywhere from $38 per barrel to $82.

Even though Shell is trying to be conservative with its long-term capital plans, including to ensure a stable and slowly rising dividend, global market conditions may not allow it to achieve its goals.

Closing Thoughts on Royal Dutch Shell

There are very few energy companies that can match Royal Dutch Shell’s impressive track record of steady and (slowly) rising dividends over time. The company’s integrated nature, globe-spanning diversification, improving balance sheet, and increasing LNG focus mean that it is likely to be a source of steady high-yield.

That being said, when it comes to integrated oil companies, Exxon Mobil and Chevron are arguably superior choices for most high-yield income investors. These businesses have superior long-term track records of capital allocation and possess attractive dividend qualities (no stock dividends, much faster payout growth rates) that more than offset for Shell’s somewhat higher yield.

Therefore, low-risk income investors looking for exposure to oil might want to consider Exxon or Chevron as better alternatives.

Leave A Comment