Founded in 1961, Lancaster Colony (LANC) is a specialty food maker that owns several niche dip, bread, frozen roll, crouton, dressing, and flatbread brands, including Marzetti, New York Bakery, Sister Schubert’s, Flatout, Aunt Vi’s, Reames, Mamma Bella’s, Romanoff, and Chatham Lodge.

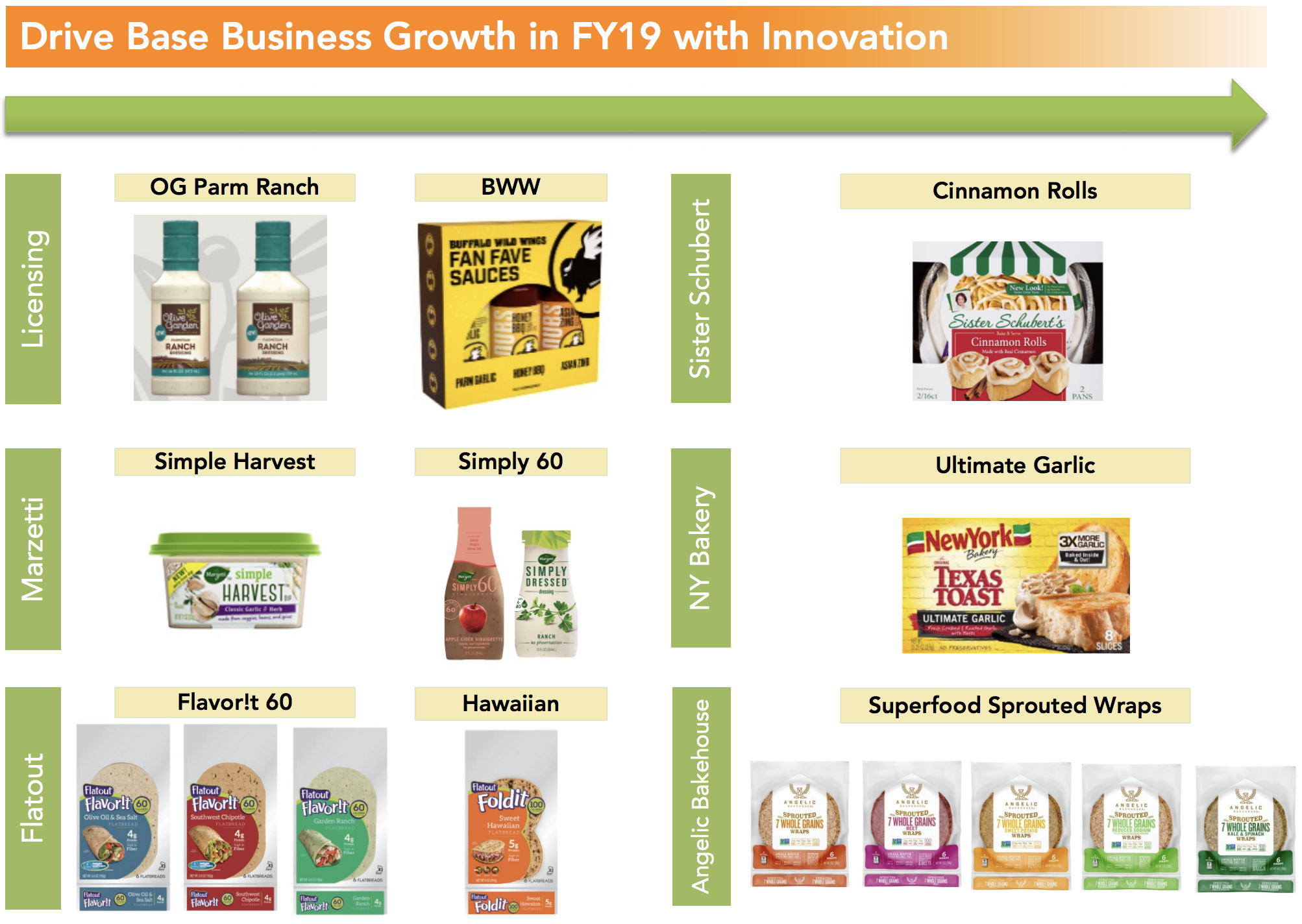

In addition, Lancaster makes licensed products including Olive Garden dressing, Jack Daniel’s mustard, and Hungry Girl Flatbreads.

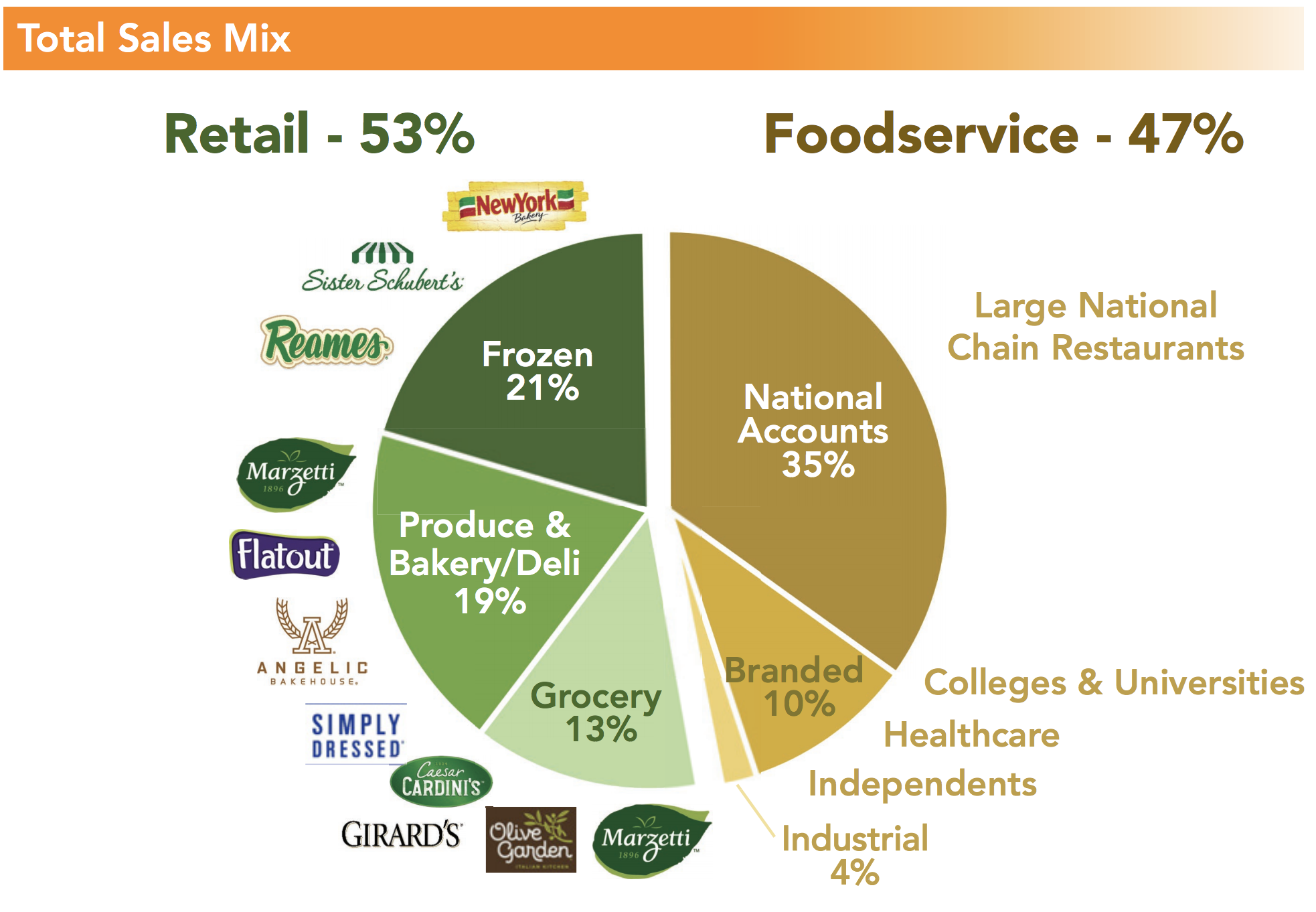

Lancaster’s products are distributed through retail grocery channels, as well as to 17 of America’s 25 most popular national restaurant chains. In 2017, 68% of sales were in non-frozen foods, with 32% coming from frozen foods. In 2017, 95% of sales were generated in the U.S.

With 55 consecutive years of annual dividend increases, Lancaster Colony is a dividend king.

Business Analysis

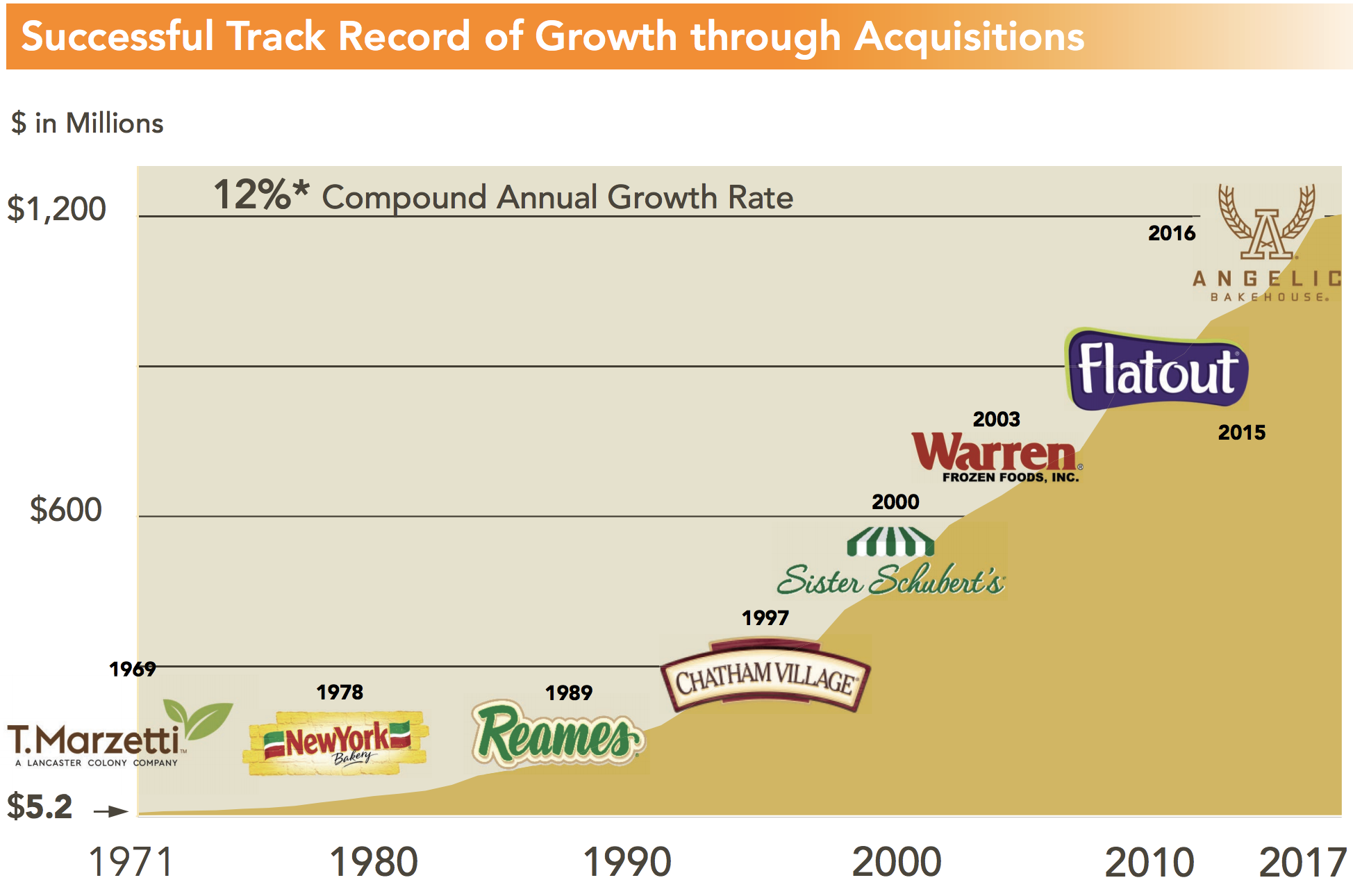

Food companies are a defensive sector, meaning that their sales usually hold up well during a recession (people always have to eat). Over the past 57 years, Lancaster has managed to achieve impressive revenue growth thanks to its strategy of making occasional acquisitions of leading niche brands that are popular with the consumer tastes of the day.

Lancaster usually avoids giant acquisitions which can result in overpaying for growth and be very challenging to execute well. For example, its latest purchase was Angelic Bakehouse in 2016, a manufacturer and marketer of premium sprouted-grain bakery products. This $35 million acquisition of a company whose healthy products are in demand with Millennials (the largest U.S. generation) is a good example of how Lancaster achieves its long-term growth.

Prior to Angelic Bakehouse, Lancaster bought Flatout for $92 million in 2015. Flatout is a fast-growing niche producer of flatbreads which have been growing in popularity in recent years. Most of Lancaster’s acquisitions are paid for in cash, and the companies it acquires are usually debt free (Lancaster has no debt on its balance sheet).

Once a company is acquired, Lancaster plugs its popular products into its large distribution network and throws its marketing dollars behind it to help drive organic sales growth. However, management spends its marketing dollars judiciously, and advertising costs historically run about 3% of revenue each year. Thanks to its selectivity on acquisitions and sharp marketing focus, Lancaster’s brands command No. 1 market share in many of its key markets. That includes:

- Flat/healthy/pita bread: 22.4% market share (next biggest rival 14.2%)

- Croutons: 36.7% (next biggest rival 27.7%)

- Frozen garlic bread: 40.1% (next biggest rival 15.3%)

- Frozen rolls: 51.2% (next biggest rival 30%)

- Produce dip: 82.5% (next biggest rival 10.6%)

One of the major keys to Lancaster’s success has been its ability to adapt to evolving consumer preferences over the years.

For example changing consumer tastes have meant that the center of the grocery store, including pre-packaged dry goods and frozen foods, are in decline. In contrast, produce, meat, dairy, and deli are thriving. Lancaster has been focusing on expanding its produce and deli offerings in recent years and they now make up about 40% of sales. Future organic sales growth and acquisitions should help increase that mix to more than 50% over time.

Going forward, Lancaster’s growth plan calls for a three-part strategy. First, the company plans to continue growing organically via launching new products umbrellaed by its popular brands and via its successful licensing deals.

Next, the company wants to continue streamlining its manufacturing and supply chains via a six sigma approach. This is a data-driven process in which consistency and reliability are highly stressed (one mistake in a million). Lancaster has its own six sigma corporate training program, which helps employees learn how to maximize supply chain efficiency and source input costs in the lowest possible way. Thanks to this approach, in the past year the company reduced its costs by about 7%, which is roughly in line with management’s long-term goals.

Finally, Lancaster plans to continue looking for opportunistic acquisition candidates. Management seeks to buy popular brands that the firm can acquire and plug into its large supply distribution. In addition to a good track record of executing on previous acquisitions, Lancaster enjoys a major competitive advantage in that it has no debt on its balance sheet. As a result, management has significant financial flexibility when it comes to investing in growth projects and making acquisitions.

Given its small size and the still highly fragmented nature of the specialty food industry, Lancaster should be able to achieve organic sales growth of about 2% to 3%, with acquisitions potentially doubling the overall growth rate.

Factoring in future margin growth from ongoing cost cutting and improving economies of scale, Lancaster could achieve high single-digit to low double-digit annual growth in earnings per share over the coming years. With the company’s payout ratio hovering near its long-term average of 50%, Lancaster’s dividend will likely grow at a similar pace.

Overall, in a highly competitive industry, Lancaster Colony has managed to generate a modest moat, driven by its disciplined focus on acquiring top brands that successfully cater to shifting consumer tastes, as well as consistent cost-cutting efforts. With a debt-free balance sheet and a product portfolio that is performing fairly well, especially compared to its larger peers, the company seems well-positioned to continue delivering impressive payout growth and strong total returns.

Key Risks

While Lancaster’s success over the last 50+ years has been impressive, there are several risks to consider before investing in the company.

Most notably, the food business in particular is a slow-growing one, which means that even with popular niche products, the majority of Lancaster’s sales, earnings, and cash flow growth stems from acquisitions.

As Lancaster continues growing in size, it becomes harder for its small-scale acquisitions to move the needle. In fact, over the past decade the company’s best sales growth in a year was 8%, and over the past five years Lancaster’s average rate of revenue growth has been about 4%.

That’s about three times slower than the company’s long-term average. As a result, fast earnings growth is also going to be harder to come by and largely driven by management’s abilities to increase economies of scale and drive costs out of the business. However, that may not be so easy.

One of the main challenges that all food companies face is volatility in input costs, specifically food raw materials and shipping expenses. Over the last few years these costs have been falling which has been a boost to the company’s margins.

However, now food prices are rising and a shortage of truckers is causing a sharp spike in shipping costs. The good news is that Lancaster’s lean supply chain has helped to keep operating margins relatively stable but they are now starting to slip. Normally food companies with strong brands pass on rising costs to their customers but this may be harder to due in the future for two reasons.

First, Lancaster is heavily reliant on just a few key distributors for much of its sales. For example, Walmart (WMT) and McLane (a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary and food distributor) made up 17% and 16% of 2017 sales, respectively. Lancaster sells its products to these distributors at wholesale prices. Both companies, but especially Walmart, have very strong pricing power and are looking to squeeze suppliers to help stabilize their margins, especially in the age of e-commerce.

The other major risk to Lancaster’s pricing power is changing consumer tastes. Specifically, Millennials are increasingly focused on fresh and healthier foods. Lancaster is all over this trend, but Millennials are also less brand loyal than previous generations. Therefore, Lancaster is going to have to keep adapting its brand portfolio over time to keep “on trend” and avoid the kind of organic sales declines that many larger good companies are facing now.

In addition, the rising popularity of private label (generic) food brands, including those owned by major retailers like Target, Walmart, Kroger, and Costco, is a potential threat to Lancaster as well. Not only are these products usually cheaper than name brands, but they are more profitable for the retailer. This trend could further erode Lancaster’s pricing power.

Finally, it’s worth repeating that acquisitions have been a major growth driver for Lancaster over the years. Each acquisition brings its own unique risks around integration and overpaying for growing brands in strong sectors, such as healthier organic foods.

Many larger food companies are desperate to buy growth and could bid up the prices of the kinds of companies that Lancaster has historically sought to acquire. Should management overpay for a large acquisition and fail to realize expected synergies, investors would likely no longer award the stock such a premium valuation multiple as they lose some faith in the firm’s capital allocation skill.

Closing Thoughts on Lancaster Colony

Lancaster Colony is a small food company that few people know about. However, the company’s strong portfolio of well-known brands and disciplined management team have done a great job of profitably growing the company for nearly 60 years.

Along the way, the firm has managed to deliver one of the most impressive dividend growth records with payout raises every year since 1963. The stock has handily beaten the market as well with a 15% annualized total return over the past 30 years (compared to the S&P 500’s 10% return).

With a very strong balance sheet, a low payout ratio, and a reasonable long-term growth plan, Lancaster Colony represents one of the best food dividend stocks in the market. The company has been holding up much better to recent changes in consumer tastes that have been bedeviling larger and less nimble food conglomerates, and management should have no trouble continuing to deliver consistent and safe income growth for the foreseeable future.

Leave A Comment