Founded in 1832, Bank of Nova Scotia (BNS) is one of Canada’s dominant banking institutions. The firm provides a broad range of advice, products, and services, including personal and commercial banking, wealth management and private banking, corporate and investment banking, and capital markets.

The bank, commonly referred to as Scotiabank, has about $900 billion in assets and serves over 24 million customers via approximately 3,000 branches operating in nearly 50 countries. Approximately 55% of the bank’s revenue is generated from net interest income (i.e. lending operations), with the remaining 45% from non-interest income sources including credit card fees, mutual funds, investment management, underwriting fees, trading revenues, and more.

Scotiabank has three primary business units:

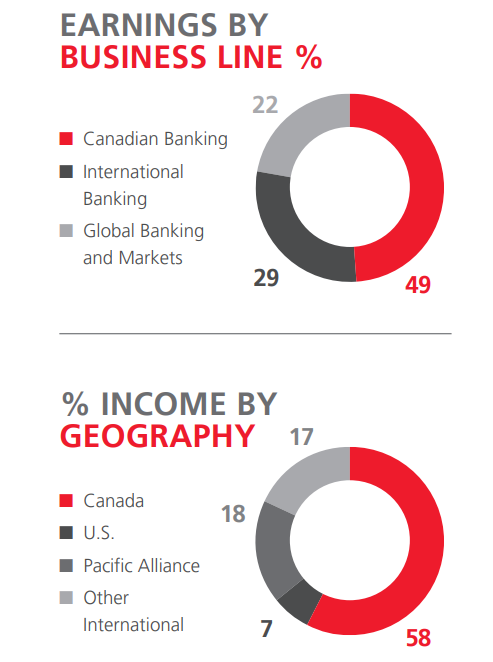

- Canadian Banking: (46% of revenue, 50% of earnings): retail consumer banking products including, debit and credit cards, checking and savings account, personal, auto, and mortgage loans. Small business and commercial lending. This segment also provides asset management services within Canada including: private customer asset management, online brokerage, full-service brokerage, pension, and institutional asset management.

- International Banking (38% of revenue, 30% of earnings): retail consumer, small business, and commercial banking outside of Canada. Also operates asset management businesses all over the world.

- Global Banking and Markets (17% of revenue, 20% of earnings):serves global capital markets (bonds and stocks), including debt and equity issuances, merger & acquisition consulting, corporate restructuring consulting, prime brokerage and treasury services, and custodial accounts for corporate, government, and institutional clients.

Among the major Canadian banks, Scotiabank is among the most internationally-focused, with just 60% of assets in its core Canadian business.

In 2017, most of the company’s sales and earnings continued to be generated in Canada. However, the faster growth rate of its international banking and global markets divisions has been steadily increasing the bank’s international diversification over time.

Business Analysis

Banking is largely a commodity product in the U.S., with consumers and businesses seeking access to dependable financing at the lowest interest rate possible. Banks with the largest low-cost deposit bases (i.e. cheap sources of funding to use for lending), most efficient operations, and conservative risk management practices tend to be best off.

Unfortunately, significant regulation and intense competition (there are more than 9,000 U.S. banks) tend to reduce the level of profitability that is possible. However, even stricter regulations in Canada, where Scotiabank generates close to 60% of its net income, create just the opposite effect.

For example, the Canadian banking sector is known for its stability, even sailing through the global financial crisis with relative ease (no Canadian banks failed or required government bailouts). In fact, Canada hasn’t had a banking crisis since 1840, largely due to strict regulations that cement the largest six banks as an effective oligopoly.

For one thing, Canadian regulators set very strict underwriting and credit standards, while also forcing banks to eat more of their own cooking. For example, Canadian banks are required by law to hold more loans (including mortgages) on their own books, rather than securitize (i.e. sell) them to third parties. As a result, lending practices tend to be far more conservative.

Home mortgages, which account for over 20% of Scotiabank’s assets, also require a minimum downpayment of 5%, and any mortgage without at least 20% down payment requires default insurance. Scotiabank is particularly disciplined as demonstrated by its average mortgage down payment of over 40%.

Besides mortgage rules, stricter credit score lending standards are also in place because the Canadian government insures all home loans under 1 million CAD against default. These conservative practices are one reason why Canadian banks suffered far less than many other financial institutions in 2008-2009.

When combined with their impressive scale and geographic diversification across the country, Canada’s largest banks enjoy durable competitive advantages, despite offering similar products and prices.

These behemoths enjoy some of the lowest cost sources of funding (massive deposit bases paying little interest), have thousands of retail locations across the country to cheaply acquire new customers, and have expanded their operations into hundreds of different product lines to continue growing. Smaller rivals struggle to compete with the giants’ prices, services breadth, and reputation.

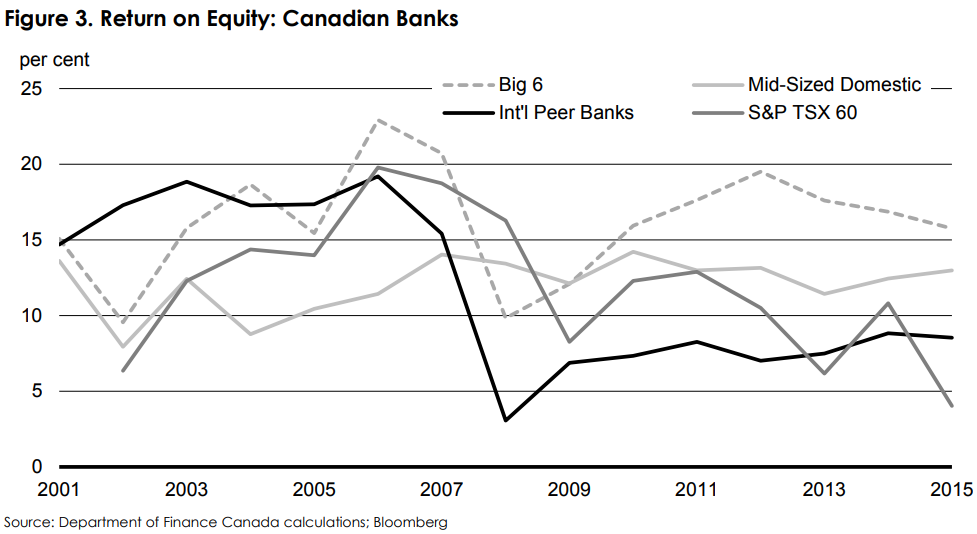

As you can see below, Canada’s big six banks (the dashed line) have generated solid profitability throughout all types of economic environments for many years. They have also earned a superior return on equity compared to smaller Canadian banks, international peers, and the corporate sector overall.

Canadian banks tend to enjoy a much higher return on equity (the key banking profitability metric) than their U.S. counterparts as well. Given the greater number of U.S. banks competing with each other, plus the onerous regulations that were implemented following the financial crisis to reduce risk, most U.S. banks earn a return on equity around 10% to 12%.

While regulations are even stricter in Canada, the major banks here enjoy more meaningful economies of scale and less competition which support a return on equity that is nearly two to three times higher than in the U.S. Part of their higher profitability is due to the low-cost structure of Canadian banks.

A bank’s efficiency ratio (operating costs/revenue) is a key profitability measure, for example. In the U.S., most big banks have efficiency ratios of 55% to 65%, and international banks that hit 60% are considered very lean operations. In Canada, most big banks have efficiency ratios between 50% and 55%, with Scotiabank achieving a 53.9% efficiency ratio in 2017.

Scotiabank is Canada’s third largest bank, behind only Royal Bank of Canada (RY) and Toronto-Dominion Bank (TD). The firm’s market share position in most retail banking segments is 3rd, with the exception of auto loans where it is the largest player.

Despite its somewhat smaller scale, Scotiabank’s return on equity was 14.6% in 2017, which is well above most U.S. banks’ profitability, as well as management’s long-term target of 14%. In Canada, Scotiabank’s return on equity is 24%, about double the profitability of most large U.S. banks.

Scotiabank’s conservative management team is led by CEO Brian Porter. Mr. Porter has been with Scotiabank since 1981 and served as the firm’s chief risk officer during the financial crisis. He spent most of his tenure working in international banking and global capital markets.

Under his leadership, the bank has focused on three areas in particular. The first is maintaining one of the safest balance sheets in the industry. This is why the bank’s common equity tier 1 ratio (shareholder equity + retained earnings/risk-weighted assets), or CET1, is 11.5%.

A bank’s CET1 ratio is arguably its most important risk metric. Under the post-financial crisis Basel III international banking accords, CET1 creates a standardized way of judging how well capitalized a bank is. For context, the U.S. Federal Reserve, which regulated all U.S. banks, has a minimum CET1 requirement of 8.5% to 9.5% (depending on a bank’s size and complexity).

This number was determined by advanced annual stress tests, which simulate a worse global recession than occured in 2008-2009. It’s now considered a good global banking standard that is likely to result in a large bank being able to weather any economic storm and remain solvent (i.e. not need a bailout).

Canadian bank’s CET1’s range from 11% to 12%, about 50% above the U.S. and international standards. Scotiabank’s ratio is among the highest in the industry and is one reason why the firm enjoys an A+ credit rating from S&P, one of the highest ratings of any bank in the world.

But a strong balance isn’t the only way the Scotiabank stays safe. The other key factor is strong loan underwriting standards. For example, the bank’s provision for loan losses (how much it thinks it will lose on loans) is extremely low (0.42%), stable, and currently beneath its five year average (0.46%).

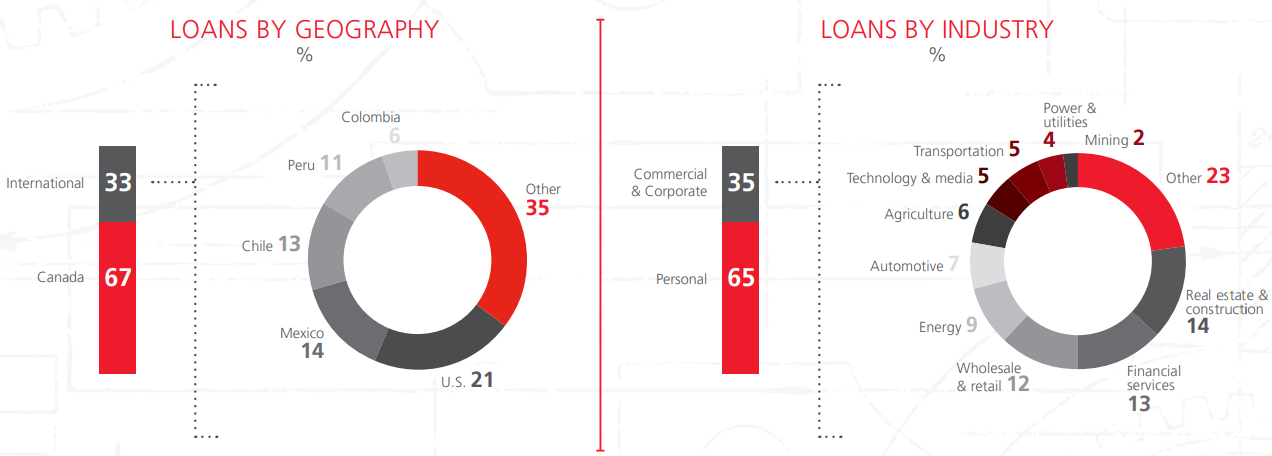

The bank’s loan portfolio is also very diversified, with a strong focus on personal lending (65% of loans) and a nice mix of industry exposure on the commercial side. While most loans are made in Canada, international lending (33% of loans) is an important focus for the firm.

The bank has been aggressively expanding into Latin America, which accounts for over 40% of its international loans. Scotiabank has made numerous acquisitions in this region, including Citigroup’s Columbian credit card business, and 2017’s purchase of BBVA Chile for $2.2 billion. These deals will make Scotiabank Chile’s fourth largest retail bank and Columbia’s No. 1 credit card issuer. In addition, the bank plans to eventually grow its Asian operations to about 30% of revenue, compared to 23% today.

However, international banking, especially in emerging markets, has much higher risk. As a result, loan losses that are about five times as great as in Canada and about three time as high as in the U.S. today. Management believes the company achieve good risk-adjusted profitability in these markets because lending operations enjoy a much higher net interest margin compared to developed nations.

Of course, breaking into a new market means that a bank initially lacks economies of scale, so management’s profitability hopes are a long-term goal. However, Scotiabank has made strong improvements to its international banking, raising its ROE from 11% in 2014 to 16% in the most recent quarter.

With CEO Brian Porter having spent most of his time in emerging market banking (nearly 20 years worth of experience), Scotiabank is arguably the best positioned of any Canadian bank to grow profitably and safely in the world’s fastest-growing markets.

The other major initiative Mr. Porter is leading is in aggressive investment into technology and cost savings. No other Canadian bank spends as much on technology investment as Scotiabank.

In 2017, the company dedicated 11% of revenue (over $3 billion) to financial technology including: AI-based cyber security and data analysis, mobile banking applications (in over 30 countries), and even blockchain experiments. The company’s long-term goal is to spend 12% of revenue on tech investments.

Technology is one of the cornerstones of management’s long-term cost cutting plan, too. For example, management has a target of over 70% digital adoption, (customers banking online), which would drive over 50% of total business. This allows the bank to operate with less capital intensity, such as not needing so many physical branches.

In addition, the company announced a major restructuring in 2016 called the Structural Cost Transformation (SCT) initiative.

Management is doing an exhaustive review of its entire business structure with a goal of eliminating $1.7 billion in annual costs. So far the company has exceeded its goals by a wide margin. Not only is SCT designed to boost net income by 20+% by 2019, but management also believes it can help Scotiabank achieve its long-term goal of an efficiency ratio under 50%.

For a bank that generates about half its income outside of Canada, even today’s efficiency ratio is impressive. And if Scotiabank can achieve an efficiency ratio under 50% by 2021, than it will become one of the world’s leanest and most profitable international banks.

Importantly, the bank’s management remains steeped in a highly conservative and disciplined banking culture that will hopefully allow Scotiabank to enjoy the benefits of strong international growth. All without risking the bank’s underlying safety.

As a result, the bank’s shareholder-friendly dividend policy should continue rolling on. For example, Scotiabank raised its dividend 43 times in the last 45 years, with flat dividends only during the financial crisis. Going forward, management thinks the bank can achieve 7% annual earnings growth, which means the company’s long-term dividend growth potential is also about 7% to 8%.

The bottom line is that Scotiabank, like its large Canadian peers, is an extremely well-managed company that has delivered predictable returns and dividends for shareholders over many decades.

And with the strongest exposure to international banking, but helmed by one of the most experienced emerging market bankers in the world, Scotiabank has one of the longest and strongest potential growth runways of any Canadian bank.

Key Risks

First, it’s important to point out that as a Canadian company, Scotiabank pays its dividend in Canadian dollars. This creates some currency risk in that a stronger U.S. dollar might decrease the effective dividend amount for American shareholders, at least in the short term (each quarterly dividend is converted from Canadian dollars to U.S. dollars when it is paid, based on prevailing exchange rates).

In addition, like all Canadian stocks, Scotiabank investors will face a 15% foreign dividend tax withholding, except in retirement accounts such as IRAs and 401Ks. Tax treaties between the U.S. and Canada allow U.S. investors to potentially recoup this withholding, but it can be a complicated and lengthy amount of paperwork at tax time.

As for risks to the bank itself, there are several to consider. First, like all banks, the company’s profits are largely tied to the health of the economies in which it operates. While Scotiabank is the most diversified of Canada’s big banks, its revenue and earnings can still be negatively affected by global downturns.

For example, during the global financial crisis the company’s sales and earnings fell by 6% and 19%, respectively. This caused the bank to freeze its dividend. However, the dividend was safely maintained as the company remained highly profitable and the dividend payout ratio was just 48% in 2009.

Economic downturns in Latin America may become a bigger concern for the bank going forward, given its large growth ambitions in that region. In the past decade, Latin America has enjoyed relatively calm and stable politics, as well as economic growth.

However, the region has been rocked by commodity price declines and significant political turmoil in the past. In 2014 alone, for example, the bank had to take a one-time charge of over 500 million CAD on loan losses in Argentina.

And keep in mind that there is no guarantee that Scotiabank can continue its strong growth in overseas markets, including Latin America. While the recent acquisition of BBVA Chile effectively doubles its market share in that country, the firm remains just the fourth largest bank in that country.

Similarly, in most of Latin America Scotiabank is the fourth to sixth largest bank, far behind Banco Santander (SAN) or government-supported banks. The bank will likely need to compete on price to win market share, which could put a cap on how profitable it can become in such markets.

Management has done a good job of disciplined underwriting and maintained a stable and relatively low (for the region) loan loss ratio. However, the bank’s loss ratio might rise significantly during the next economic downturn.

The same is true for Asian loans, which Scotiabank hopes will generate 30% of company-wide revenue within the next few years. As the bank becomes more diversified into emerging markets, the predictability of its earnings could decline somewhat.

The other major risk all banks face is regulatory in nature. Most recently, Canadian regulators raised capital requirements ahead of the Basel III full phase-in coming in 2022. This means that Scotiabank’s forward CET1 ratio will rise to 11.8%, slightly lowering its short-term profitability. In the future, regulators in other countries could increase their own capital requirements which might impinge on the bank’s profitability.

Closing Thoughts on Bank of Nova Scotia

Canadian banks have proven to be some of the safest in the world over the years. Virtually all banks are complex financial institutions with cyclical earnings and murky balance sheets, but Canadian banking culture is very conservative, which should help Scotiabank’s dividend profile remain relatively strong even during a severe global economic downturn.

While Scotiabank’s industry-leading exposure to emerging markets creates risks investors need to keep in mind, it also potentially gives the firm one of the best long-term growth runways of any major Canadian bank.

Combined with management’s disciplined approach to safe banking practices, Scotiabank could be an interesting income growth idea for investors who are comfortable investing in this complex industry.

To learn more about Bank of Nova Scotia’s dividend safety and growth profile, please click here.

Leave A Comment