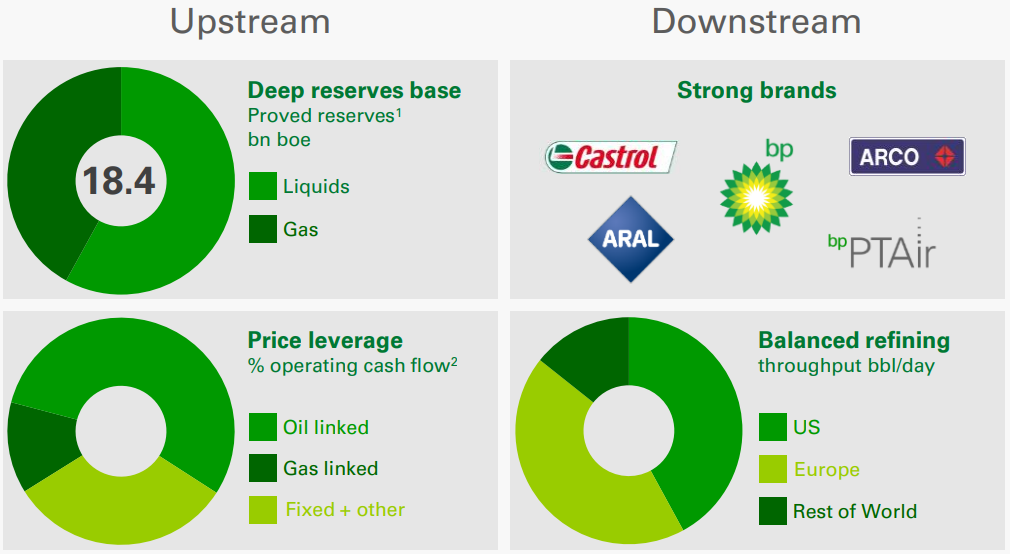

Founded in 1889 and based in London, British Petroleum (BP) is one of the largest integrated oil and gas companies in the world with sales in excess of $240 billion in 2017. The company operates in over 70 countries and has proven oil & gas reserves of 18.4 billion barrels of oil equivalent (about 20 years’ worth of current production).

BP has three business segments: upstream oil & gas production, downstream (refining, lubricants, fuels, and petrochemicals), and its 19.75% stake in Rosneft, the Russian oil giant.

- Upstream (39% of 2017 pretax profit): BP’s activities in oil and natural gas exploration, field development, and production (2.5 million barrels per day of oil equivalent production, excluding Rosneft). This segment is very sensitive to the global price of oil.

- Downstream (54% of pretax 2017 profit): consists of global marketing and manufacturing operations, selling fuels (BP has over 18,000 retail gas stations), lubricants (sold to automotive, industrial, marine, and energy markets globally), and petrochemicals (used by others to make essential consumer products such as food packaging, textiles, and building materials).

- Rosneft (7% of 2017 pretax profit): Rosneft is the largest oil company in Russia and the largest publicly traded oil company in the world, based on hydrocarbon production volume. Russia has one of the largest and lowest-cost hydrocarbon resource bases in the world.

As you can see, the company is highly diversified with a pretty even mix between oil & gas production and downstream sales.

Business Analysis

The oil industry is marked by large fixed capital costs and very cyclical revenue, earnings, and cash flow. This makes it a challenging industry for dividend investors to do well in.

However, BP has managed to overcome numerous obstacles in recent years, including massive industrial accidents and the worst oil crash in decades. A key to BP’s success has been its ability to respond to challenging industry conditions through very aggressive cost cutting.

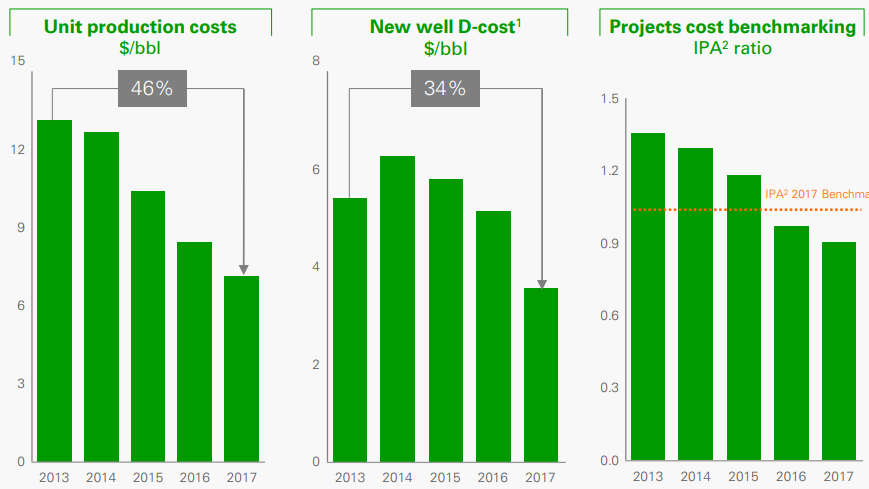

Since 2014, the company has reduced its operating costs by $7 billion per year and plans to spend about $16 billion annually on capital expenditures over the next few years. That’s 36% less than its 2013 spending peak, when oil prices were north of $100 per barrel. Unit production costs are down 46% since 2013 with costs at their lowest level since 2006.

Thanks to these cost-cutting measures, BP’s current dividend breakeven production cost is about $50 per barrel. Or to put it another way, as long as the price of Brent oil (the global standard) is above $50 per barrel, BP’s free cash flow is expected to cover the company’s dividend and keep it sustainable.

BP’s focus is on slow decline, high-margin production, such as liquified natural gas projects and shale gas production out of the U.S. Haynesville shale formation. For instance, at $3 per thousand cubic feet, BP estimates that it can earn 40% internal rates of returns on U.S. shale gas. This is why BP has quadrupled its Haynesville shale acreage and plans to nearly quadruple its production from that formation in the next four or five years.

The company has also been making good progress on optimizing its oil exploration budget. For example, despite drastically cutting its exploration budget, BP made six potentially commercial discoveries in the past two years including: two in the UK, two in Trinidad, one in Egypt and one in Senegal. These discoveries totaled about 1 billion barrels of oil equivalent and helped BP achieve a reserve replacement of 143%, compared to 109% last year.

If an oil company’s reserve replacement rate (new discoveries/total production) is under 100%, then its reserves will decline over time and production levels will gradually fall. But if the reserve replacement is over 100%, then reserves grow over time and allow for production to increase.

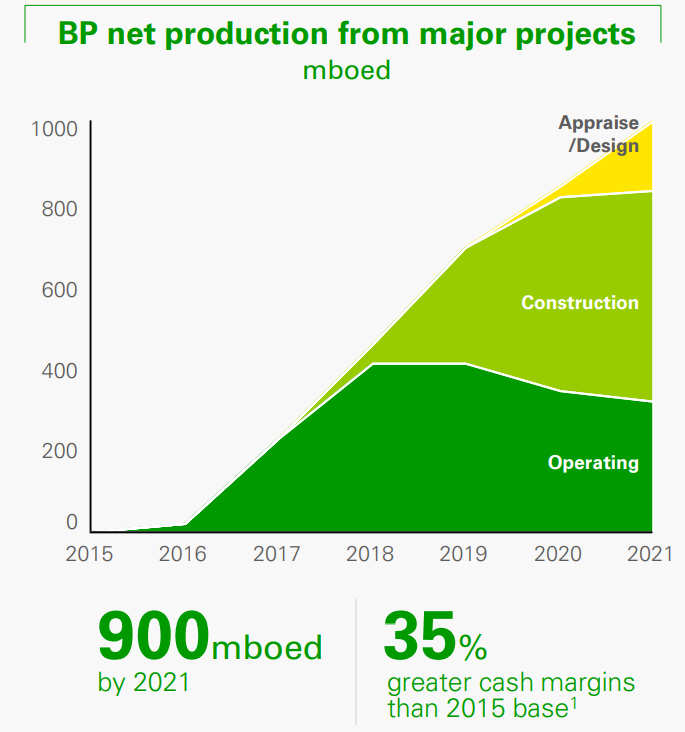

The company brough six major projects online in 2016, seven in 2017, and has 21 more scheduled to come online by 2021. These are expected to generate 35% higher profitability per barrel of oil equivalent compared to 2015. More importantly, BP estimates that it will be able to boost its daily oil production by 900,000 barrels, or 36% in the next four years (5% annual production growth).

Thanks to expectations for rising cash flow and ongoing cost-cutting measures, including more data-driven drilling techniques, BP thinks it can lower its dividend production breakeven price to $35 to $40 per barrel by 2021 (from $50 today). That should help make the dividend safer even in the event of another prolonged decline in oil prices.

Management’s long-term goal is to increase the firm’s return on invested capital from 5.8% in 2017 to at least 10% by 2021. The combination of lower costs and higher production means that at an average oil price of $55 per barrel in BP’s upstream business should be producing about $13.5 billion in free cash flow by 2021.

The company has also been streamlining its downstream business and expects to generate an additional $3 billion a year in free cash flow by 2021. All told, BP thinks it can achieve about $23 billion a year in free cash flow by 2021, assuming oil prices remain at $55 per barrel or higher.

That, in turn, would mean that BP’s free cash flow dividend payout ratio would fall to a secure level below 30% and even give the company the potential to raise its dividend in the coming years.

However, while BP’s current dividend is indeed generous and appears sustainable for now, be aware that there are numerous risks that could make the stock a subpar income investment.

Key Risks

As with any major oil company, there are numerous risks to be aware of.

First, BP’s business model is inherently cyclical with extremely volatile earnings. Even the downstream businesses, including refined products and petrochemicals, are commoditized and BP has no pricing power.

In other words, investors are relying on management to be highly capable of making smart capital allocation decisions and executing over time. However, BP has a relatively poor track record relative to some peers such as Chevron (CVX) and Exxon (XOM).

One example is the company’s troubling past regarding safety. Prior to the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster, BP had been fined by OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) over 700 times, compared to Exxon which was fined just once, per Business Insider. And speaking of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon tragedy, investors can’t forget that this industrial disaster will remain an albatross around BP’s neck for a long time.

The April 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion killed 11 workers and resulted in the largest oil spill in history. After the explosion, it took BP 80 days to get the spill under control, resulting in the largest oil spill in history (about 5 million barrels).

BP set aside $32 billion for clean up costs and legal liabilities, which forced it to sell off tens of billions of dollars in assets and slash its dividend 29% in 2010. However, the total cost of that disaster is now expected to be $61.6 billion, of which BP has paid a total of $38.6 billion so far including $5.4 billion in 2017.

Per management’s guidance, the company will be paying an additional $23 billion for this industrial disaster through 2035 before all legal liabilities are settled. BP expects to pay just over $3 billion in 2018, with oil spill cash payments stepping down to around $2 billion in 2019 and about $1 billion thereafter.

The good news is that BP has made improving safety a top priority to avoid similar costly disasters in the future. For example, in 2011 the company had 33 Tier 1 reportable safety accidents, which the company has reduced to 18 by 2017. But the concern is that while BP may be investing more into higher safety standards now, its enormous legacy asset base means that it might face future major industrial accidents that could result in enormous legal liabilities and once more emperil the dividend.

Another concern for BP investors is management’s historically poor track record of capital allocation, especially relative to American peers such as Exxon Mobil, which has consistently proven the industry’s top capital allocator. In fact, even if BP achieves its ambitious goal of nearly doubling its returns on invested capital by 2021, it still won’t come close the 20% return that Exxon thinks it can hit in the coming years.

Good capital allocation can be a challenge for all oil companies since major exploration and development projects are incredibly complicated, costly, and can run into numerous problems that put them behind schedule and over budget.

These problems can be political in nature (dealing with various foreign governments who want a big piece of the pie), or due to various problems with execution, which can cause projects to end up years behind schedule and well over budget.

Then there is BP’s large exposure to Rosneft (7% of BP’s pretax profit in 2017) which has been facing tougher U.S. sanctions since 2014. As a result, Rosneft has effectively been cut off from Western Capital markets and forced to borrow record amounts of debt at much higher interest rates.

In fact, Rosneft’s latest bond offerings were for 10-year notes at an 8.35% interest rate. Rosneft currently accounts for 31% of BP’s consolidated oil production, and should oil prices crash in the future, it might have a hard time maintaining its own production while refinancing its costly debt.

Speaking of debt, be aware that BP’s balance sheet is also highly leveraged. For example, the firm’s debt/EBITDA ratio is 2.4 compared to the industry average of 1.8. The good news is that BP still has a A- credit rating, and its cash flows should easily service its debt.

However, management has said that it wants to use BP’s growing free cash flow to pay down debt in the future, which means less cash available to increase the dividend which has now been frozen for four years. Analysts don’t expect BP to raise its dividend until 2022, although the company has hinted it may consider a dividend increase as early as 2018.

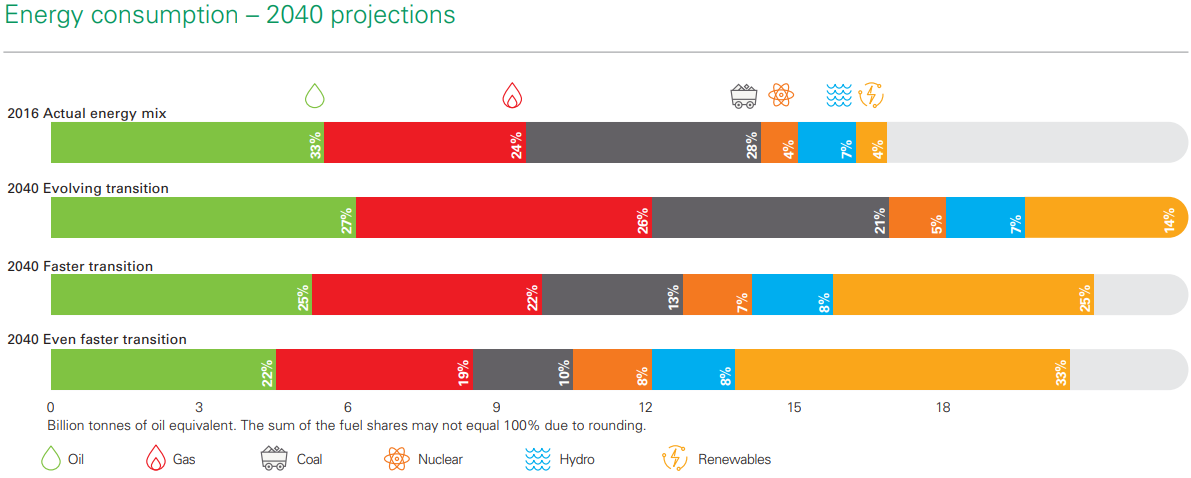

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that BP’s long-term growth plans hinge on the highly uncertain future of the world’s global energy mix.

BP needs to make long-term investment decisions on assets that will have to recoup their construction and operation costs over decades. However, given the world’s accelerating transition to cleaner energy it’s impossible to say when global oil demand will peak.

For example, BP’s current investment plans anticipate oil & gas still representing 53% of the world’s global energy mix by 2040, compared to 54% in 2016. However, the company has admitted that a faster transition to renewable energy might mean that figure comes in closer to 40%, which could drastically decrease the company’s long-term growth prospects and profitability.

Overall, BP’s risk profile, especially with regards to its dividend safety, has improved meaningfully over the last few years. The company’s efforts to take out costs, slash capital expenditures to the bone, divest “non-core” assets, improve its balance sheet, and offer a scrip dividend program (22% of shareholders elected to receive their dividends in shares rather than cash in 2017) helped BP hunker down as best it could during the oil crash.

Most importantly, the macro environment is also cooperating. With Brent crude averaging over $70 per barrel thus far in 2018, up significantly from its $54 per barrel average in 2017, BP’s dividend breakeven cost has much more breathing room, and the company’s profits are surging.

However, commodity prices are notoriously volatile, and the long-term effects of BP’s potentially excessive cost cuts, asset divestitures, and dilutive scrip program have yet to be seen. The company remains the lowest quality and riskiest of the oil majors, even if its payout is now on stronger ground.

Closing Thoughts on BP

BP has made many important changes since the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster and the worst oil crash in over 50 years. Aggressive cost cutting, improved safety, and a long-term plan for future production growth should position the company to maintain its dividend even if oil prices head lower once again.

That being said, BP’s troubling long-term track record on safety, as well as its history of substandard profitability and far less impressive dividend growth than rivals such as Chevron or Exxon, mean that conservative investors might want to consider the other oil majors for their high-yield portfolios.

To learn more about BP’s dividend safety and growth profile, please click here.

Leave A Comment