Founded in 1903 in Dearborn, Michigan, Ford (F) is the third largest automaker by revenue with approximately 7% global market share. In 2017 the company sold more than 6.6 million cars, SUVs, and trucks under the Ford and Lincoln brands in North America, South America, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

While Ford is a global company, the vast majority of its sales (over 60%) and profits (approximately 100%) are derived from its North American business, where its market share is by far the greatest:

- North America: 13.9% market share

- South America: 8.9%

- Europe: 7.5%

- Middle East & Africa: 3.9%

- Asia Pacific: 3.4%

Ford Financial Services is the company’s financing arm, designed to help customers finance the purchase of new vehicles. In 2017, this segment generated $2.3 billion in pre-tax profits that accounted for 32% of the company’s total operating earnings.

Business Analysis

The auto industry has historically been a terrible one for conservative investors seeking safe and growing dividends for several reasons.

First, the industry is extremely capital intensive, with enormous fixed costs stemming from the large factories required to manufacture vehicles. These plants need to be running at high utilization rates to generate sufficient returns on investment. However, the cyclical nature of auto sales means that the industry goes through periodic boom and bust cycles, creating wild swings in margins and profitability.

The second strike against automakers is the incredibly competitive nature of the industry, which results in very few enduring competitive advantages for any firm. Auto manufacturers tend to have little pricing power, in part because they need to keep their costly factories pumping out vehicles to stay efficient, which results in uncapped industry supply.

As a result, these businesses have historically found themselves slashing prices for consumers and selling vehicle fleets at low margins to rental companies during industry downturns to rid themselves of excess inventory.

The U.S. auto industry has been especially vulnerably over the years thanks to a large reliance on higher margin, larger vehicles such as trucks and SUVs, which accounted for nearly 80% of Ford’s U.S. auto volume last year. The sale of such vehicles can be especially fickle, especially during times of recession or high fuel prices.

That being said, Ford has come a long way from the dark days of the financial crisis. While the company didn’t have to take a bailout from the U.S. government (as Chrysler and GM had to), the company was still heavily burdened by: excessive capacity, way too many product lines, and enormous legacy costs such as the United Automobile Workers (UAW) healthcare and pension liabilities.

Under former CEO Alan Mulally, the company undertook a three-pronged turnaround effort.

The first step was shedding itself of its massive medical liabilities. This occured as part of bankruptcy negotiations with the UAW during the financial crisis. The big three U.S. automakers established a health trust (now operated by the UAW) in which they made a one-time payment of $56.5 billion to cover $88 billion in future healthcare liabilities for 750,000 retirees and their dependents.

As a result, Ford’s legacy liabilities were drastically reduced, which meant that it could become more profitable and competitive with international and lower-cost rivals in the future.

The second part of the turnaround strategy was a major focus on cost cutting and streamlining operations. For instance, in 2007 virtually all of Ford’s sales were built on more than two dozen global vehicle platforms, across numerous brands such as: Ford, Lincoln, Volvo, Land Rover, Jaguar, Aston Martin, and Mercury.

Under Mulally, Ford sold off all of these non-core brands, retaining only Ford and Lincoln. This allowed the company to streamline its platforms to just nine, with eventual plans to get that down to eight. Management expects this consolidation to reduce product development costs by 20% over the long term.

Essentially, Ford is now leveraging more new products off of fewer design platforms, meaning it can create or redesign models at far less cost and then amortize their development expenses by selling them worldwide in greater volumes.

The final piece of the turnaround was focusing on improved products that consumers in all nations wanted to buy. This partially meant nicer designed cars, utilizing the former designs that Ford previously owned under the Aston Martin and Jaguar brands, for example.

However, the biggest turnaround initiative with Ford’s vehicles was their quality, specifically with a greater focus on reliability. After all, Japanese car makers such as Honda (HMC) and Toyota (TM) built their global empires by focusing on highly reliable vehicles that provide many years of relatively trouble-free ownership.

In 2007, J.D. Power & Associate’s initial quality study of new auto customers found that Ford’s cars had an average of 221 problems in the first year per 100 vehicles. That was slightly above the industry average of 216, but far below industry leaders such as Buick, Lexus, and Cadillac, which led the industry in reliability with 145, 145, and 162 problems, respectively.

However, 10 years later things have really turned around for Ford when it comes to reliability. While the entire auto industry has drastically improved its quality (average first year problems down from 216 to 97), Ford’s score of 86 indicates a 68% improvement in reliability. In fact, today Ford’s cars are actually more reliable than Toyota’s, according to J.D. Power & Associates rankings.

All told, Ford’s turnaround has meant that automotive operating margins increased from -0.7% in 2009 to 5% in 2017. However, that’s far below the company’s long-term target of 8%. Simply put, the margin boost Ford has enjoyed has largely been from the low-hanging fruit it picked by reducing pension costs and streamlining its platforms.

Additionally, the costs of launching so many new models and redesigned vehicles also meant that capex spending basically grew in line with sales between 2010 and 2016. As a result, Ford wasn’t able to gain as much operating leverage to generate higher profit margins and cash flow.

Going forward, new CEO Jim Hackett believes that the company can reduce the growth rate of capex spending by 50% between 2017 and 2022. Part of that improvement will be driven by further streamlining.

Specifically, Ford will reduce its number of global platforms to just eight, and the company plans to offer far fewer orderable combinations per vehicle. That will mean less complexity and even greater cost amortization in the future.

In total, management believes it can squeeze $14 billion in cost savings out of Ford’s manufacturing process over the next five years, equating to nearly $3 billion a year in cost savings (around 2% of 2017 sales, for the sake of comparison).

While streamlining operations is important in such a price-competitive industry, Ford’s most important growth potential comes from its increased focus on future technology. For example, the company is investing heavily into mobility technology and electric vehicles.

In fact, by 2019 Ford’s goal is for 100% of its U.S. cars to have advanced mobility connections (to the internet). By 2020, Ford hopes to achieve the same for 90% of its global vehicles sold.

And since so many countries are now considering eventually phasing out petroleum-powered vehicles, Ford is also planning on investing heavily into electric cars.

Specifically, the company’s “Team Edison” will spend $11 billion through 2022 to create 40 electrified models (including hybrids and plug-in hybrids), including 16 fully battery-powered models.

Most of these cars are slated for overseas markets, especially China. That’s where the government has set a quota of 10% and 12% of all cars sold being electric by 2019 and 2020, respectively.

However, Ford’s Jim Hackett expects Ford’s biggest earnings growth to come in the form of innovative mobility solutions, specifically in the realm of driverless cars. The company is already testing these and hopes to have a fully marketable sedan ready to sell to fleet users such as Uber by 2019.

Hackett also believes that vehicle management as a service, or VMaaS, will serve as a major growth driver in the years ahead. Large fleets of driverless cars are expected to serve the needs of ridesharing and delivery services in the future. Ford hopes to manage these needs for fleet customers.

Hackett thinsk the global VMaaS market will eventually reach $400 billion per year and generate operating margins of “at least 20%.” If true, then with just 12.5% VMaaS market share, Ford would be able to fully replace its current profits from autosales. That’s how big this market opportunity could be for the company.

Overall, Ford has taken meaningful steps to avoid becoming an uncompetitive dinosaur at risk of extinction in the fast-moving automotive world of tomorrow. The company’s new and more adaptable management team has done a nice job of launching improved vehicles that are a hit with consumers, and that can be produced at a profit.

However, despite Ford’s improved operations and bold vision for an electrified autonomous vehicle future, investors need to realize that there remain numerous serious challenges facing the company.

Key Risks

While Ford has undoubtably done an impressive job in turning around the quality of its products and business fundamentals since the financial crisis, there remain numerous challenges ahead that could make it a poor dividend growth stock.

For one thing, Ford remains incredibly dependant on its core North American market for the vast majority of its sales and over 100% of its pre-tax profits. Over the decades, the company has been able to optimize its manufacturing and supply chain the the U.S. far better than newer markets such as Latin America, where it actually lost $784 million in 2017.

Similarly, Ford’s Middle East and Africa business lost $263 million while the long-struggling European business (very high labor costs) made just $234 million. One trouble for Ford in many of these non-U.S. markets is that consumers are usually less attracted to high-priced larger vehicles, especially SUVs.

In 2017, Ford’s average truck transaction price rose by $1,500 to $47,200 off strong sales of its redesigned Ford F-150, Lincoln Navigator, and Ford Expedition. These last two vehicles are full-size SUVs that have been enjoying strong demand thanks to the oil crash which cut the price of U.S. gas prices in half. Low interest rates have also made it easier for consumers to finance expensive vehicle purchases.

However, even these tailwinds could be waning. For example, Ford announced a 6.9% drop in U.S. vehicle sales in February 2018, including a 12% year-over-year decline in trucks.

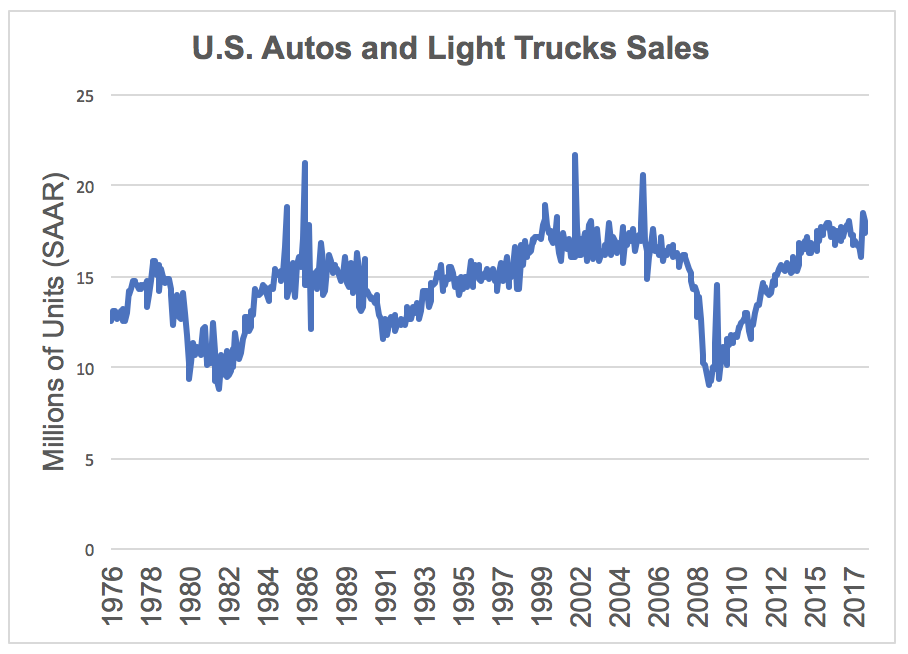

This brings us to the second major risk for Ford, which is that the all-important U.S. auto market may have peaked. You can see that U.S. sales of autos and light trucks sales have sharply recovered following the financial crisis, hovering around 17 million units at a seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) in recent years.

Most “experts,” including General Motors’ chief economist, expect demand levels to remain similar or only slightly down in 2018. The record age of vehicles on the road (over 11 years versus 9.6 years in 2002), low gas prices, rock bottom interest rates, and an improving economy could keep the good times rolling for much longer than most people expect.

However, no one can really forecast when the next inevitable downturn will occur with much accuracy.

But what about China? The Chinese automarket is indeed the largest in the world (29 million vehicles sold in 2017, up 3%) and is expected to grow to 35 million vehicles sold by 2025. However, Ford may not be able to achieve strong sales and earnings growth from China’s booming automarket.

For example, in 2017 the company’s China sales volumes were down 7% to just 1.1 million cars, representing 4.2% market share. Increased competition also forced Ford to cut prices, resulting in Chinese net margins falling 25%.

Going forward, almost every major automaker has plans to push hard into the Chinese market, including major domestic manufacturers who have strong support from the government. As a result, Ford shareholders can’t count on China to necessarily be a key profit driver in the future.

Massive competition in the automotive industry also means that companies are constantly having to invest heavily in launching new or redesigned products. In 2017, Ford launched just 11 products, but the firm plans on 23 global product launches in 2018 and 76 in 2019.

The higher cost of these redesigns (during a time when its global sales volumes are declining) means that Ford’s adjusted earnings per share are expected to decline by more than 10% over the next year.

Combined with the company’s high fixed capital costs (and potentially higher input costs thanks to recently announced U.S. steel tariffs), Ford’s earnings are likely to be highly volatile, which doesn’t help the company’s ability to sustain, much less grow, its dividend over time.

For example, since 1980 Ford has cut or suspended its dividend no less than four times: in 1980, 1991, 2002, and 2006. Each of these periods were marked by substantial declines in the U.S. economy and auto sales, which saw sales volumes decline by as much as 30% in 1980 and 2009.

The good news is that Ford has implemented a hybrid dividend policy, in which it pays out 15 cents per share quarterly, plus a special dividend to achieve a 40% to 50% adjusted EPS payout ratio. The company believes its policy will make the current quarterly dividend sustainable in the long term.

The company has modeled, via a “stress test,” a hypothetical future U.S. industry downturn in which sales decline by as much as 36% from 2015’s highs. The company projects that Ford’s large cash reserves ($26.5 billion at end of 2017) and large revolving credit lines ($10.9 billion), should make the dividend safe during such an event.

Ford’s Internal Stress Test

However, note that when Ford came up with this variable dividend scenario, the company had different management. The old regime hadn’t yet planned on investing $11 billion into designing 40 fully or partial EVs by 2022.

These higher development costs, combined with the new CEO’s greater focus on driverless cars and Vehicle management as a service, could ultimately mean that Ford now has greater investment needs in the future. In other words, the company’s dividend may not be immune to a reduction in a future industry downturn.

After all, if U.S. vehicle sales are currently falling during a strengthening economic environment, then the industry’s sales volumes might end up coming in below even Ford’s worst case assumptions during a future recession.

In fact, the very megatrend that Ford is now hanging its hat on with regards to future growth, driverless cars, might end up being its biggest risk of all. That’s because in the future subscription autonomous car services might very well end up drastically changing consumer spending habits.

For example, according to AAA, the average cost of owning a car in the U.S. is about $8,400 a year, or $700 a month. And the cost of owning a pickup truck or SUV (Ford’s biggest cash cows) can be $1,000 to $1,500 more per year.

In the future, if a driverless robo taxi service can allow consumers to spend far less (say 50%) of the cost of owning a personal vehicle, than U.S. vehicle sales could decline by a significant amount as more consumers opt not to directly own vehicles themselves.

As a result, Ford’s VMaaS plans might not become a nice source of additional profit growth, but rather the company’s chief source of revenue and profits.

While new CEO Jim Hackett is confident that Ford is well positioned to dominate this important industry of the future, keep in mind that there is no guarantee that this will prove true. That’s because key rivals like General Motors are also investing heavily into EVs and driverless cars. Ford may end up competing on price in VMaaS just as it does with its regular cars, and thus the fat 20% operating margins that Hackett predicted in the past might not be realized.

There’s also no guarantee that Ford can ever become as competitive in electric vehicles and autonomous cars as it has been in traditional gas/diesel powered vehicles. After all, GM has announced it plans to launch 20 electrified vehicles of its own in the next five years. Volkswagen plans to launch 15 new EVs as well and has declared it’s budgeting $40 billion for the effort (nearly four times what Ford plans to spend).

Two other concerns to consider are that Ford has seen a lot of management turnover recently, potentially due to its dual class share structure. The Ford family owns just 4% of Ford’s total shares, but because they own all 70 million or so class B shares, they retain 40% of voting control.

Therefore, they have an outsized influence on how the company is run. And while their interests appear aligned with those of common shareholders, their influence may also be the reason for Ford’s relatively high managerial turnover.

For instance, Ford is now on its third CEO in five years, with Mark Fields replacing Alan Mulally in 2014. Fields was a 28-year veteran of the company who helped to deliver Ford’s record profits in 2015 and also had a grand vision for the company as a leader in electric vehicles and driverless cars.

However, in what some analysts referred to as a coup, Chairman Bill Ford decided that Field’s wasn’t acting aggressively enough on this vision. According to Ford, “we need speed…and to take hard actions.” Thus Hackett, who only joined Ford’s board of directors in 2013 (before that he was a top executive at an office furniture company), was charged with delivering on this faster growth and innovation.

A key concern that dividend investors have is that should all these management changes result in a shift in company priorities, then the previous guidance of a safe dividend during future downturns might not hold true, especially as the industry’s status quo appears to be evolving faster than ever before.

Closing Thoughts on Ford

Ford has done an impressive job of turning around its previously bloated operations to become a far more streamlined, innovative, and financially healthy company.

However, the auto industry is one that is generally not well suited to paying generous, safe, and steadily growing dividends.

The cutthroat nature of the competition, very high capital costs, and cyclical demand trends have resulted in dividend cuts being a common occurrence in the past. When combined with the meaningful uncertainty that the industry’s business model faces going forward, payout cuts may continue to be an issue.

While Ford’s shares typically look “cheap” and offer a high yield, conservative income investors, especially those focused on capital preservation, may be better off avoiding this stock, or at least keeping it as a relatively small position as part of a well-diversified dividend portfolio.

To learn more about Ford’s dividend safety and growth profile, please click here.

It would be interesting given this analysis to see a best-of-breed analysis that is country agnostic, eg. Toyota, Volkswagon, GM, etc. Thanks Brian.