CVS Health (CVS) is one of America’s most dominant healthcare players. The company operates the nation’s second largest pharmacy chain with over 9,800 retail locations. CVS is also one of the nation’s largest pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs), with over 94 million plan members who used CVS to file 1.3 billion medical care claims in 2017. CVS acquired Caremark RX for $21 billion in 2006 to become the second biggest PBM.

The pharmacy benefits business provides vital services to employers and insurance companies by determining which drugs are covered for patients and negotiating price discounts with drugmakers.

In 2017, the majority of CVS’s sales came from its PBM segment, which, thanks to a faster growth rate than its retail pharmacy business, is likely to only become more important over time.

However, because of the much smaller operating margins in its PBM segment, CVS still generates the majority of its operating income and free cash flow from its retail business.

- Pharmacy Services: 62% of sales, 42% of operating profit, 3.6% operating margin, 9% revenue growth last year

- Retail/Long-Term Care: 38% of sales, 58% of operating profit, 8.1% operating margin, -2% revenue growth last year

Business Analysis

CVS’s legacy retail pharmacy business has historically grown though industry consolidation, allowing it to create a massive nationwide store network on par with Walgreens Boots Alliance (WBA). Offering customers convenience and leveraging its scale to keep prices affordable proved to be an effective strategy.

However, CVS management recognized years ago that rising healthcare costs would increasingly put pressure on every aspect of the medical sector to cut costs, which is why it bought Caremark RX for $21 billion in 2006.

This acquisition made CVS the second largest PBM in America. By becoming more vertically integrated and achieving economies of scale, CVS was able to generate very impressive earnings, cash flow, and dividend growth over the past decade.

Why was the PBM segment such a boon to CVS? Mainly because, as rising costs and increased regulatory complexities under the Affordable Care Act (i.e. ObamaCare) set in, many organizations, including health insurance companies such as Aetna (AET), are willing to outsource the nitty gritty logistical details of managing various health programs to PBMs such as CVS.

This is because PBM’s are responsible for saving their clients as much money as possible, through things like negotiating price breaks with pharmaceutical companies and medical component makers.

And better yet they are willing to sign long-term contracts, like the 12-year deal that Aetna inked with CVS back in 2010, which gives management a lot of future cash flow predictability with which to plan its further growth efforts.

In other words, CVS has evolved beyond just a chain of pharmacies and stores, turning into one of the most important names in U.S. health insurance. Thanks to the continued expansion of its PBM business, CVS is able to generate large economies of scale, which means some of the lowest per claim costs in the industry. That helps CVS maintain market share which only further grows its moat and helps maintain high retention rates with PBM customers.

Even as the medical sector as a whole consolidated, driven by a growing desire to achieve greater scale and the leverage over suppliers and customers that comes with it, CVS has managed to continue growing.

In 2015, the company acquired 1,667 of Target’s (TGT) in-store pharmacies and 79 clinics for $1.9 billion. That year CVS also made its $12.7 billion purchase of PBM Omnicare, adding to that aspect of its empire as well.

However, all that growth and vertical integration hasn’t spared CVS from hitting some bumps in the road more recently. Specifically, while its PBM business continues to grow at a high-single digit clip, the pharmacy business and retail stores saw same-store sales contract by 2% to 3%.

Pharmacy same-store sales were especially hit by increased generic drug pricing pressures, driven by higher supply and some pressure from lawmakers. Generics made up 87% of CVS’s prescriptions filled in 2017, and the company earns a low margin as a middleman distributor of these drugs to customers. Thanks to continued pricing pressures, management ultimately lowered its guidance for 2018 to about 1.5% revenue growth and flat adjusted EPS growth.

Unfortunately, while CVS expects its retail business to pick up, the PBM business, which has long been the company’s main growth driver, is now expected to see revenue growth slow. And that’s despite medical claims rising to a record high of over 1.9 billion in 2018 (volume growth is being offset by downward pressure on drug prices).

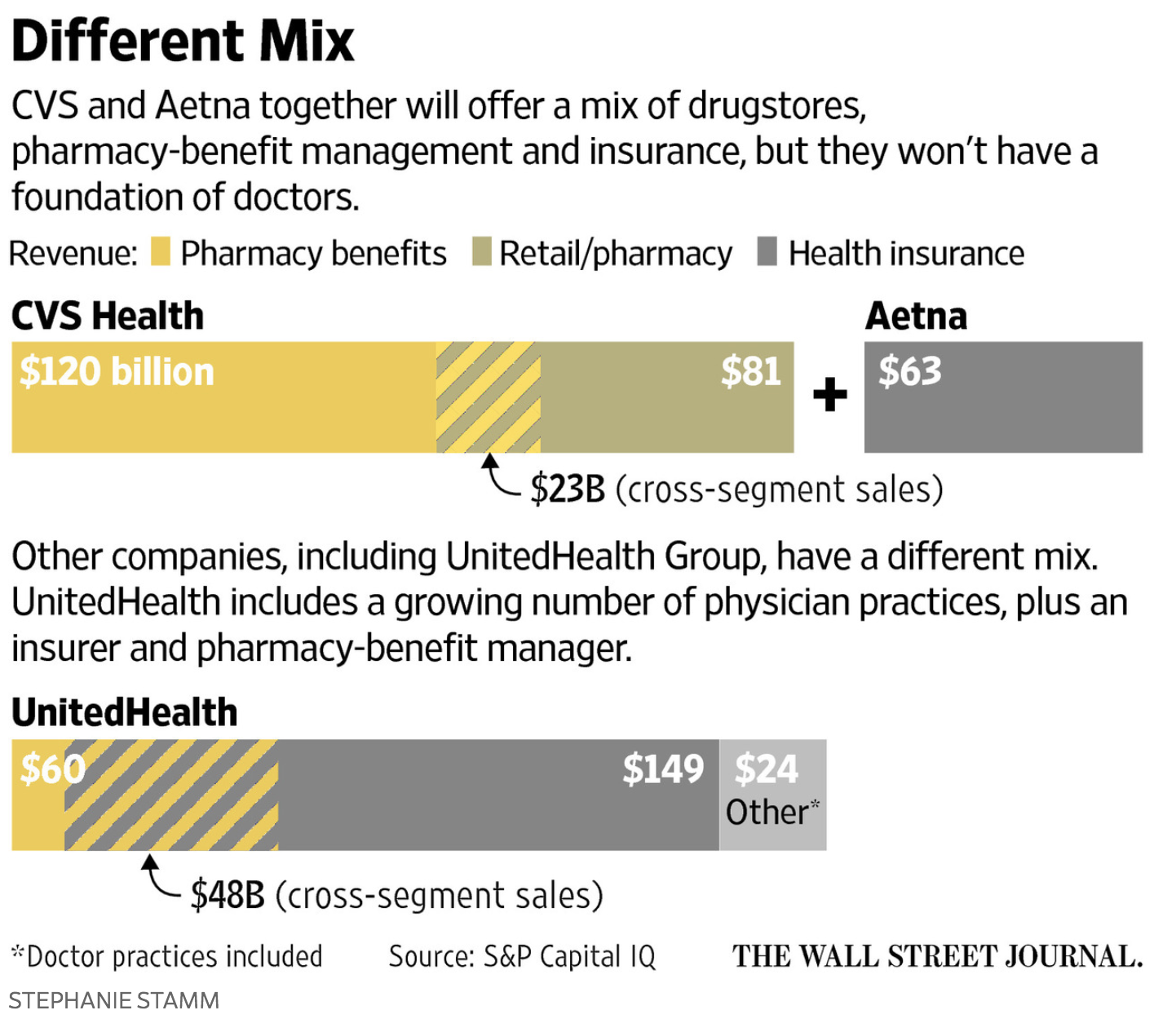

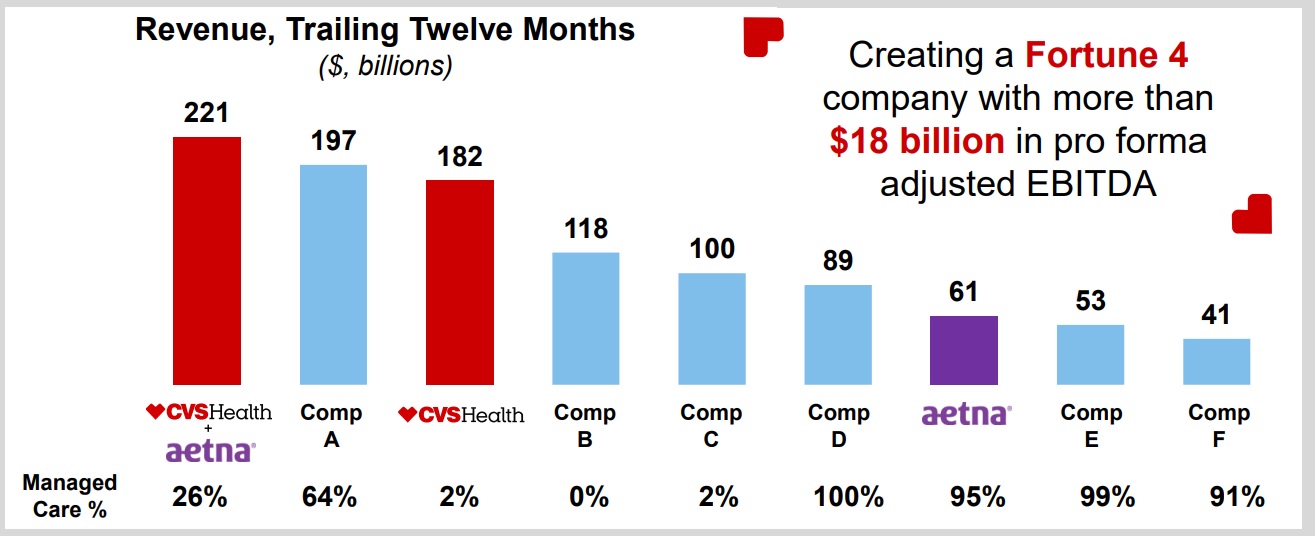

CVS is clearing facing some major growth headwinds as the medical sector evolves and focuses even more on lowering costs. In an effort to ensure continued relevance and increase its vertical integration even further, CVS announced in late 2017 it was buying insurance giant Aetna for $77 billion (including debt assumption).

This deal combines two very different companies, providing CVS with greater diversification as the healthcare landscape evolves. If the acquisition isn’t blocked by regulators, CVS would benefit from locking in Aetna’s large base of insured customers for its PBM business and retail drugstores.

CVS also hopes to evolve its store locations to be able to provide more types of medical care for patients, which could reduce costs and make it an even more attractive PBM partner for large employers.

If nothing else, the deal provides CVS with some diversification in the even that Amazon and others successfully enter and disrupt the pharma industry.

If the deal is approved, it will make CVS an even more dominant force in healthcare, with over $220 billion in revenue and larger adjusted EBITDA margins than what CVS currently enjoys.

CVS believes that by combining its massive network of pharmacies, clinicians, and PBM business with Aetna’s nearly tens of millions of insurance members, it will be able to achieve $750 million a year in cost savings by the end of the second full year.

Part of these savings are expected to come from combining the massive databases of CVS and Aetna, which management believes can help create better (and lower cost) patient outcomes. For example, 20% of Medicare hospital discharges end up being readmitted due to errors in diagnosis or treatment, which represents a massive financial drain on the medical system.

In addition, with much larger scale (more customers), CVS would have greater bargaining power with drug and medical device suppliers. In other words, if CVS becomes big enough, it has potential to squeeze out additional costs throughout the medical supply chain, reducing costs for its customers (or at least lowering the growth rate of Aetna’s annual insurance premium increases).

CVS expects the deal to become accretive to adjusted EPS by the end of the second full year after closing (2020 if it closes in 2018), and analysts believe that the larger CVS might be able to achieve long-term revenue and earnings growth of 11% and 15%, respectively.

In other words, CVS acquiring Aetna appears to be a smart strategic move on paper. If everything goes well, it could return CVS to the kind of strong double-digit growth in its bottom line that could make it an appealing long-term dividend investment.

However, there are numerous large risks to the industry, as well as the Aetna merger itself.

Key Risks

A rapidly-aging population (10,000 Americans achieve retirement age a day) means that U.S. medical spending is expected to soar from $3.5 trillion today to more than $5 trillion over the next decade, representing about 20% of the entire U.S. economy, according to Ventas.

The projected $1 trillion to $2 trillion increase in spending is not only a result of the baby boomer generation aging, but also decades of rising medical costs. Not surprisingly, pressure has increased on the entire medical sector to somehow cut costs, and the result has been massive industry consolidation across every part of the medical supply chain.

However, this consolidation hasn’t necessarily resulted in higher profits for medical companies because the underlying factor driving the mergers and acquisitions is a desire for scale so that they can demand lower prices from their suppliers.

A large part of this is because as boomers age into retirement, Medicare covers more and more of America’s healthcare spending. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has spent the last several years instituting changes in how the Federal government pays for medical care, with a greater focus on outcomes-based reimbursement, as opposed to pay for service.

In other words, the rising cost of healthcare means that the Federal government (which covers about 50% of Americans via Medicare and Medicaid) is increasingly reducing how much it will pay per patient, forcing companies throughout the medical industry to adapt to an increasingly austere business climate.

This can be seen with CVS’s struggles with lower pharmacy sales and profits, as patients are increasingly being pushed to lower cost generic drugs.

As America’s aging demographics continue to put a strain on Federal entitlements, government-driven price caps could be mandated that would blow a big hole in the value proposition of PBMs. Specifically, the idea that a PBM such as CVS can help health consumers cut costs via negotiating with medical suppliers.

Indeed, the PBM business model has been coming under increased scrutiny. They are supposed to lower prices for consumers, but the industry remains quite opaque with where and how profits are moving around. The article linked to above provides a great look at PBMs’ unique risks.

The Aetna acquisition may make sense strategically, in that it will indeed make CVS the largest medical company in America and provide some diversification. However, the deal is still extremely risky given its financial and operational risks.

In fact, Morningstar estimates that CVS is paying double what Aetna is worth, while taking on $45 billion in additional debt (to pay the cash component) to do it. This means that CVS’s leverage ratio (Debt/Adjusted EBITDA) will rise from 2.2 to 4.6, which is far above the industry median of 2.1.

Management has said that it plans to deleverage as fast as possible to the low 3 range, and the dividend is frozen at its current level until that happens. This brings an end to CVS’s 14-year streak of annual increases and is a deep disappointment to shareholders who were attracted to the previous 20+% payout growth rate.

But what about the supposed stronger growth and accretion to earnings that occurs after two years? Well, there is a lot of risk here as well because those optimistic estimates are based on two main assumptions.

First, that management can achieve its $750 million a year in synergistic cost savings (not guaranteed by any means), and that both Aetna and CVS will see accelerating top and bottom line growth relative to the last few years. If either one of these assumptions fails to happen, then CVS investors may be waiting far longer for the deal to become profitable.

The reason that there is so much uncertainty about the growth of CVS and Aetna accelerating is because the need to cut costs is starting to cause many new ideas to enter the medical sector, most notably Amazon (AMZN) apparently trying to leverage its expertise in delivery into a new prescription distribution business.

And then there’s the recent announcement that Jeff Bezos (CEO of Amazon), Warren Buffett (CEO of Berkshire Hathaway), and Jamie Dimon (CEO of JPMorgan Chase) are teaming up to create a non-profit company to provide comprehensive medical coverage to employees of their companies (they employ 1 million people collectively).

These three business legends, each with an exceptional track record of operational excellence, believe that their combined skills in finance, insurance, and technology/logistics can help achieve lower and higher-quality of care than currently exists within the existing health insurance system.

If the bold plan succeeds, it’s possible that other companies will be allowed to join, and perhaps eventually individual Americans. This could provide to be yet more downward margin pressure for America’s medical sector.

The bottom line is that CVS is being forced by very challenging conditions into a deal that has a lot of risks and big downsides, but unknown upsides. And even assuming the deal receives regulatory approval, then CVS shareholders will be stuck with zero dividend growth for several years. The company will also become far less financially flexible as it has to divert all of its post-dividend free cash flow to deleveraging as quickly as possible.

CVS ultimately seems to be taking an enormous and risky strategic gamble, not to mention sacrificing its impressive dividend growth track record to do so. Only time will tell whether or not the payout ever returns to its former double-digit growth rate.

Closing Thoughts on CVS Health

Historically, CVS has been very good at adapting to fast-changing and challenging industry conditions. The company’s skilled management team has proven itself to be very shareholder-friendly, especially in regards to it long track record of very fast dividend growth.

However, in recent years margin pressures caused by a large-scale pushback against rising medical costs have squeezed all medical companies and necessitated major (and sometimes highly questionable) M&A activity.

That certainly applies to CVS’s potentially game-changing acquisition of Aetna, which has very large risks associated with it. It will take years for investors to know whether or not this was a smart capital allocation decision, but what is certain, that, at least for now, is that CVS is no longer a dividend growth stock.

Combined with all of the uncertainties surrounding potential changes in medical policy at the Federal level (plus the potential success of the Bezos/Buffett/Dimon initiative), conservative income investors are probably best off avoiding CVS.

At the end of the day, it’s just really hard to grasp all of the changes happening across the entire healthcare value chain. From increased drug price scrutiny to reimbursement rate pressures and the potential for PBM business models to structurally change in ways that would harm CVS’s long-term profitability, there are a number of concerns bubbling up that make it difficult to gain conviction in CVS’s long-term growth potential (and value).

To learn more about CVS Health’s dividend safety and growth profile, please click here.

Leave A Comment