Founded in 1849, Pfizer is one of the world’s largest drug makers, with over 95,000 global employees, more than 60 manufacturing facilities, and medications sold in over 125 countries.

The company’s annual sales exceed $50 billion and are grouped into two business segments:

Innovative Health (60% of sales and 62% profits): produces patented medicines to treat various therapeutic areas, including internal medicine, vaccines, oncology, inflammation and immunology, and rare diseases.

This unit drives Pfizer’s overall growth because it produces all of the company’s largest sellers, including a number of medications with more than $1 billion in annual sales. Compared to other pharma and biotech companies, Pfizer’s portfolio is nicely diversified by treatment area and drug type, reducing its risk profile.

Pfizer’s largest drugs in this segment are the Prevnar family of therpeutics (10.5% of company-wide sales; pneumococcal vaccines), Lyrica (8.7%; epilepsy), Ibrance (6.2%; breast cancer), Eliquis (4.7%; blood thinner to reduce risk of strokes), and Enbrel (4.7%; arthritis).

Aside from Ibrance and Eliquis, Xtandi (1.1%; prostrate cancer) and Xeljanz (2.4%; arthritis) are key growth drivers that are early in their patent-protected lifecycles.

This segment also includes Pfizer’s consumer healthcare business (6.5% of sales), which consists of dietary supplements, pain management, gastrointestinal, and respiratory and personal care products marketed under some of industry’s most trusted names. However, this business may not stay with Pfizer for long as management is exploring selling or spinning it off.

Essential Health (40% of sales and 38% of profits): markets Pfizer’s legacy medications that have lost or will soon lose patent protections, such as Lipitor (3.5% of company-wide sales; cholesterol), Norvasc (1.8%; high blood pressure), the Premarin family (1.8%; menopause), and Celebrex (1.5%; arthritis).

This unit also produces and markets generic drugs, biosimilars (1% of sales; fast-growing generic versions of biological drugs), and sterile injectable products.

Outside of growth in biosimilars, sterile injectables, and emerging markets, this segment is challenged due to continued headwinds from products losing marketing exclusivity. Fortunately, this part of Pfizer’s portfolio is also nicely diversified with almost all of its drugs accounting for less than 1% of sales, helping avoid a steep and sudden drop in overall results.

In total, Pfizer’s sales are split about equally between the U.S. and the rest of the world, with the larger Innovative Health unit being slightly weighted more towards domestic sales, while Essential Health is more focused on international regions. Emerging markets account for just over 20% of company-wide revenue.

Business Analysis

In theory, blue chip drug makers make great dividend stocks because the demand for their products is highly stable and recession resistant. And with the strong growth in demand for healthcare products, courtesy of an aging global population, overall drug sales should only increase over time.

While it is very expensive to internally research, develop, run clinical trials, and ultimately commercialize a new drug, these companies can enjoy years of monopoly status with a product that should have extremely stable to growing demand. This dynamic leads to a very stable margin structure and can generate predictable cash flow to fund generous dividends.

However, drug company’s actually face many challenges when it comes to growth, specifically because of what we like to refer to as the drug hamster wheel.

Patent expirations, very strong competition from similar products (launched by rivals), and the fast growth of cheaper generic drugs mean that pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer face an uphill battle when it comes to growing their sales, earnings, and free cash flow.

Drugs that lose market exclusivity often fade quickly, so their revenue must be replaced by new drugs that find success. However, the cost of developing new drugs is extremely expensive, which is why Pfizer routinely spends about 15% of sales on R&D. As a result, the company’s fixed costs are relatively high, so its margins can be very volatile as well.

With that said, Pfizer does enjoy a solid moat, courtesy of the high development costs and complex regulatory hurdles required to bring a new drug to market (a process that can take as long as 12 to 13 years).

In other words, few companies in the world can match Pfizer’s enormous resources and technical know-how. While it’s true that patents are temporary, the high margins on patented drugs they allow while they are in effect make Pfizer a free cash flow generating machine (free cash flow margin over 20%).

Another competitive advantage Pfizer has is its very large, globally distributed sales force, which has had much success in growing its drug sales in emerging markets, which account for more than 20% of total sales today and include countries such as Brazil, Russia, India, China, and Turkey.

Developing nations are where the majority of future long-term growth is likely to come from because developed nations, while possessing fast-aging populations, are struggling with flat (or falling) population growth rates.

As importantly, Pfizer’s management is doing a good job of diversifying its business from pure patented drugs into two major growth areas, biosimilars and sterile injectables.

There are two kinds of drugs, chemical-based (derived from organic compounds, such as various proteins) and and biological (enzymes derived from biological sources). When a chemical drug goes off patent, the formula is known and can be easily replicated in any manufacturing facility around the world, resulting in margins falling off a cliff.

However, biosimilars have a distinct advantage in that after a biosimilar goes off patent, any rival attempting to recreate it must go through the same regulatory hurdles that the original biological drug had to pass through to achieve initial approval. In other words, while generic drugs are cheap and easy to make, biosimilars are far more complex, expensive, and time consuming to bring to market, even if a drug’s patent expires.

This creates a naturally wider moat around such drugs, and because biosimilar drugs are already proven market winners (the original biological drug was a blockbuster), there is less risk to developing them than with brand new medications.

This is why pharmaceutical companies are racing to get into this fast-growing and highly profitable space, and why there are over 200 biosimilars currently in development, according to Evaluage Pharma and PharmaCompass.

Pfizer got into with biosimilars in a big way with $16 billion acquisition of Hospira its 2015, which delivered it a strong biosimilar development portfolio, as well as a platform in the fast-growing (though smaller) injectables industry.

Pfizer is known as a serial acquirer (more so than most pharma companies), and in 2016 it made more than $20 billion in acquisitions, including:

- Anacor Pharmaceuticals ($5.2 billion; eczema treatment drug)

- Medivation ($14 billion; prostate cancer drug Xtandi)

- Two antibiotics from AstraZeneca (AZN)

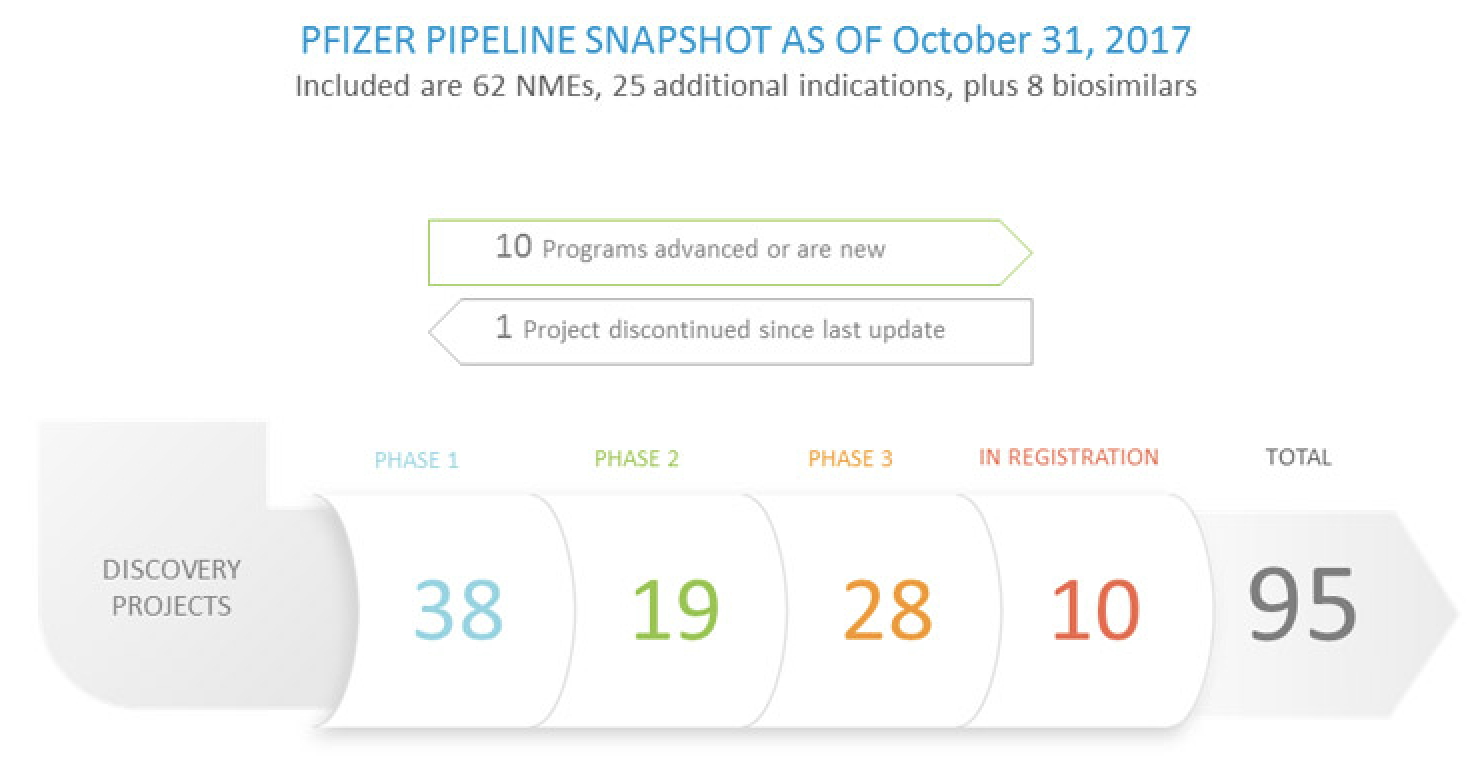

These deals helped grow the company’s development pipeline to an industry leading 95 products in development, including 15 blockbusters that could be approved for sale by regulators by 2022 and which management expects to potentially generate $1 billion or more in annual sales.

Pfizer has been transitioning its business in recent years to combat declining sales from key product, such as Lipitor, losing patent protection and facing increased generic competition. Moves to spin off its animal health business for more than $2 billion in early 2013 and the company’s renewed interest in separating off its consumer healthcare unit all point to a future in which Pfizer’s business is completely dominated by prescription drugs.

Fortunately, the company believes it is nearing an inflection point where new product launches (including the 15 potential blockbusters previously mentioned) and fewer losses from drugs coming off patent protection will drive revenue higher over the coming years.

“We expect the full-year year-over-year impact of [loss of exclusivity] to continue to be significantly lower than our recent past. We’re forecasting the impact to be approximately $2 billion in each of the next three years, about $1 billion in 2021, and then $500 million or less from 2022 through 2025. At the same time, we expect a steady flow of new products to begin to emerge from our pipeline.” – CEO Ian Read

To put those loss of exclusivity figures in perspective, patent expirations and generic competition had resulted in approximately $5 billion in annual losses for Pfizer in recent years, according to The Wall Street Journal. The new tax bill’s lower rate to bring back profits that are sitting overseas (of which Pfizer has billions of dollars) could also serve as a catalyst for Pfizer pursuing a large acquisition to further boost growth.

The bottom line is that Pfizer, as one of the world’s largest and premier drug makers, has significant competitive advantages, including massive economies of scale, access to vast amounts cheap capital (a “AA” credit rating from S&P), a well-diversified drug portfolio, and a very cash-rich business model. These factors have made the stock a popular holding in conservative retirement portfolios.

Key Risks

It’s important to realize that the pharma industry is one that is both highly capital intensive and, thanks to the periodic roll off of patents, also cyclical.

As a result, mergers & acquisitions are an especially important component of the business model for larger players. Snapping up smaller rivals with promising medications helps giants such as Pfizer grow their own drug portfolios and offset losses in market share that naturally occur due to patent expirations and rivals launching similar products.

However, with any large acquisition there is a big risk of overpaying and missing on expected synergistic cost savings, which can result in poor allocation of shareholder capital.

Pfizer’s track record is a mixed bag when it comes to such acquisitions, including:

- Its $68 billion acquisition of Wyeth in 2009 to offset the upcoming large patent cliff in 2011, which resulted in a large dividend cut.

- The failed $100 billion acquisition of AstraZeneca in 2014.

- The failed tax inversion deal to acquire Allergan for $160 billion in 2015.

In fairness to Pfizer, acquiring Wyeth was ultimately a good long-term move because it gave the company Prevnar 13, the company’s best-selling product. Better yet, as a vaccine, Prevnar faces far less threats from generic competition, and thus has more stable sales and generates important cash flow stability.

Dividend cuts like the one caused by Pfizer’s Wyeth acquisition are difficult to predict because they have to do with management’s capital allocation decisions rather than their underlying payout ratios, business fundamentals, and balance sheet.

With that said, astute investors could have anticipated management’s decision by understanding that the company would need to make a large acquisition to insulate itself from the patent cliff.

Fortunately, today’s situation isn’t nearly as dire as it was back in 2009. As previously noted, Pfizer expects its business to enjoy an inflection point over the coming years, and the company has already made several large acquisitions in recent years to rebuild its pipeline. While the future is unknowable and difficult to forecast, it would be very surprising if management made another large capital allocation decision that would force a dividend cut.

With that said, investors should also note that Pfizer has a poor record of slashing R&D once it makes a large acquisition, which can ultimately hurt long-term competitiveness.

In addition, management has flip flopped a bit on its corporate strategy. For example, in 2016 activist investors pushed for the company to sell off its consumer products business (6.5% of total company revenue), which has ten brands with more than $100 million in annual sales.

While recording lower margins than patented drugs, this division still has strong branding power and is a highly dependable source of sales, earnings, and cash flow because none of its products will ever face a patent cliff.

The company said it had decided to not sell this unit in 2016, but apparently now has changed its mind and is once more considering selling the division to a rival for as much as $10 billion or more.

In other words, if Pfizer does decide to change its mind again, investors would have to potentially worry about the permanent loss of revenue, as well as the increased volatility in the company’s top and bottom lines as it becomes even more of a pharma pure-play.

However, if Pfizer invests the proceeds wisely, such as into new product development or a successful acquisition, then the move could pay off. But given Pfizer’s past track record and the uncertainties in the patented drug industry (where even the most promising blockbusters can fail to reach market), good capital allocation is far from guaranteed.

Speaking of risks in drug development, thanks to increasing regulatory hurdles, the cost of bringing new drugs to market has been steadily rising over the decades and is now approaching upwards of $2 billion to $3 billion per drug.

There’s also the constant threat of major federal medical regulatory changes, not least of which is the uncertainty surrounding any potential repeal and replacement of the Affordable Care Act (ObamaCare). Such an action could potentially remove tens of millions of Americans from the healthcare system, resulting in less drug sales.

Even if the number of American’s with access to drugs doesn’t change, Congress could always amend current laws that prohibit Medicare and Medicaid from negotiating bulk drug purchases. This represents low-hanging fruit that could result in much lower drug costs.

While that may be great for consumers, it could squeeze the profitability of all drug companies, which have largely relied on pricing gains to boost earnings in recent years, and result in even more growth pressure (and forced acquisitive activity).

Finally, because Pfizer obtains approximately 50% of its sales from overseas, the company is exposed to currency risk. Specifically, if the U.S. dollar strengthens, some of Pfizer’s products become more expensive (i.e. less competitive), and the company’s international profits translate into fewer U.S. dollars for accounting and dividend payment purposes.

Closing Thoughts on Pfizer

The pharma industry’s complexity is enough to scare off many conservative investors, and rightly so. From industry pricing concerns to patent cliffs and blockbluster flops, there is no shortage of murky issues that can cause surprises.

With that said, Pfizer is one of the few companies that seems worth considering for income in this space. It appears that the worst of its drug-exclusivity losses are behind it, the company’s portfolio of medicines is nicely diversified, Pfizer’s drug pipeline offers a lot of potential across many different therapeutic areas, and its balance sheet remains in great shape.

All in all, Pfizer appears to be recovering well from the 2011 patent cliff by investing significant capital in R&D and acquisitions to rebuild its pipeline.

As long as management has allocated capital well by conducting in-depth market research and due diligence, the business should begin to return to stronger organic growth after years of struggling.

While Pfizer may have its challenges, as do all drug makers, ultimately the company looks like an above-average choice with a well-covered dividend in a highly defensive sector.

To learn more about Pfizer’s dividend safety and growth profile, please click here.

Leave A Comment